“Are you lost?,” an old lady at the mall asks sad-sack Renn Wheeland (Nick Jonas) during one of his omnipresent bouts of millennial ennui. It’s the kind of innocuous statement that, when revealed in stark close-up, is meant to convey a broader thematic underpinning in Robert Schwartzman’s weepy indie dramedy “The Good Half.” You see, Renn is lost, in the way so many sad white boys in movies like these are: His mom (Elisabeth Shue) has recently passed, and he’s too emotionally stunted and cynical to deal with it in any sort of healthy way. So, too, is Brett Ryland’s script, sadly, Schwartzman’s limp direction guiding a listless Jonas through a half-baked meditation on grief that feels too twee by half.

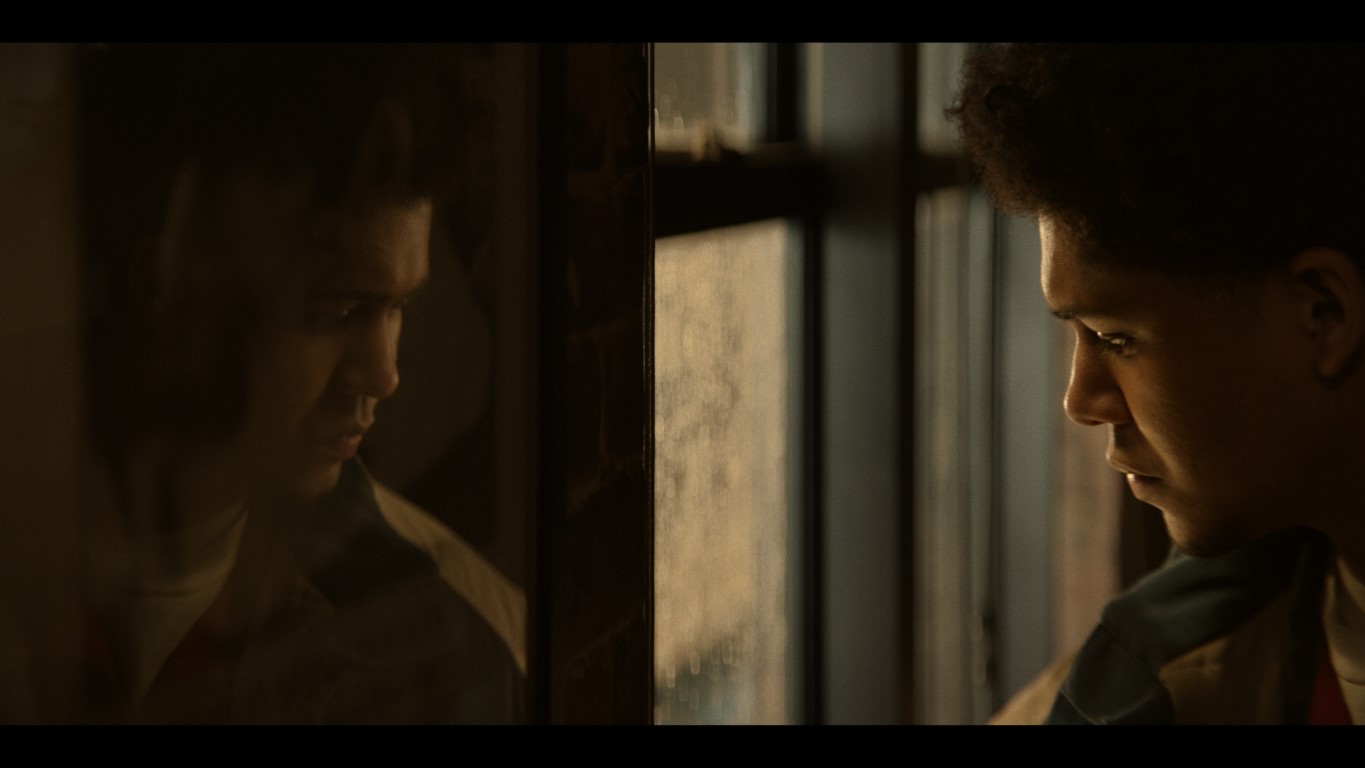

The bastard stepchild of “Garden State” and “Elizabethtown,” “The Good Half” feels too measured to work as melodrama and too mannered to be mumblecore. From its opening minutes, featuring Jonas lying expressionless in bed as the opening titles appear, Schwartzman lacquers this whole thing with a syrupy haze of melancholy, as if channeling Zach Braff on a hefty dose of Benadryl. Renn, you see, is your prototypical Disaffected White Boy, an obnoxiously passive stand-in for the screenwriter’s obviously autobiographical journey. He’s an aspiring screenwriter plugging away in LA, fighting off overtures from his boss to take a modest promotion (“you’d be supervising the payroll,” he offers) because he fears it’ll make him lose his dream. But naturally, his mother dies, and he takes the first flight out to his hometown of Cleveland, Ohio to deal with his family and bury her.

Renn’s relationship with his family, and his mother specifically, is complicated in that first-draft screenplay kind of way. In flashback, we see his mother as the kind of free-spirit that’s fun to be around but dangerous to trust: a formative memory for Renn is being abandoned at the store while Mom stole trinkets and tried on clothes she’ll just end up returning. He’s avoided seeing his family for months as Mom wasted away from cancer. So his father (Matt Walsh), stepfather (David Arquette), and sister (Brittany Snow) are all various flavors of angry at him. And his snarky, cynical attitude doesn’t help, Ryland sneaking one obnoxious quip after another in Renn’s mouth, Jonas delivering them with all the conviction of (ironically) a eulogy. Sure, he’s supposed to be masking his grief through humor, but neither him nor his family enjoy it, so we don’t either.

One of his few lifelines outside his well-meaning but thinly drawn family is Zoey (Alexandra Shipp), a quirky girl he meets on his flight home, where they bond over whether or not all ’90s action movies are masterpieces. She’s the kind of Manic Pixie Dream Girl archetype you’d think we’d left behind in the late 2000s, yet here she is with her infectious personality (she’s so likable that she makes two new best friends that morning who follow her to karaoke) and oh-so-charming witticisms (e.g. referring to their current locale as “the land of Cleve”). On top of all that, she’s a therapist, thus serving double duty as Renn’s romantic and emotional support. She’s literally tailor-made in the script to fix him, and Shipp gets little to do besides that.

Schwartzman’s approach is sluggish and poorly-paced, the film color-corrected to within an inch of its life and unable to balance the delicate tightrope act of comedy and drama that good examples of this kind of movie can attempt. Instead, it’s didactic and miserable, one scene after another hammering home the bone-simple idea that it’s not easy to grieve a loved one. The flashbacks serve little purpose but to undercut Renn’s contention that his mother “hated” her life, and the occasional slow-motion needle drop sequence feels like a limp attempt to throw a Wes Anderson or Zach Braff flourish at the film to impose some kind of style on the whole thing. It feels derivative, and just doesn’t work.

Early on, Walsh’s put-upon father confesses to Renn that he has no idea how to help his kids through their grief: “I feel like I should tell you something profound, like quoting Thoreau or something.” This line is more revealing than you’d think; “The Good Half” is desperate to say something profound about the thorny nature of grief and how it forces us to confront the scary future we face without that person we love most in the world. But there’s nothing new here that hasn’t been cribbed from better, or even just earlier, texts. Instead, like Renn himself, Schwartzman and Ryland keep themselves (and us) at a distance from the material and our characters, keeping any of us from getting any closure or finding something new to say about such a universal experience.