Death and desire collide with seductive, shivering power in Robert Eggers’ “Nosferatu,” a grandly Gothic reinterpretation of F.W. Murnau’s silent-film classic that channels the dark, psychosexual energies at the core of vampire mythology into a haunting tale of obsession.

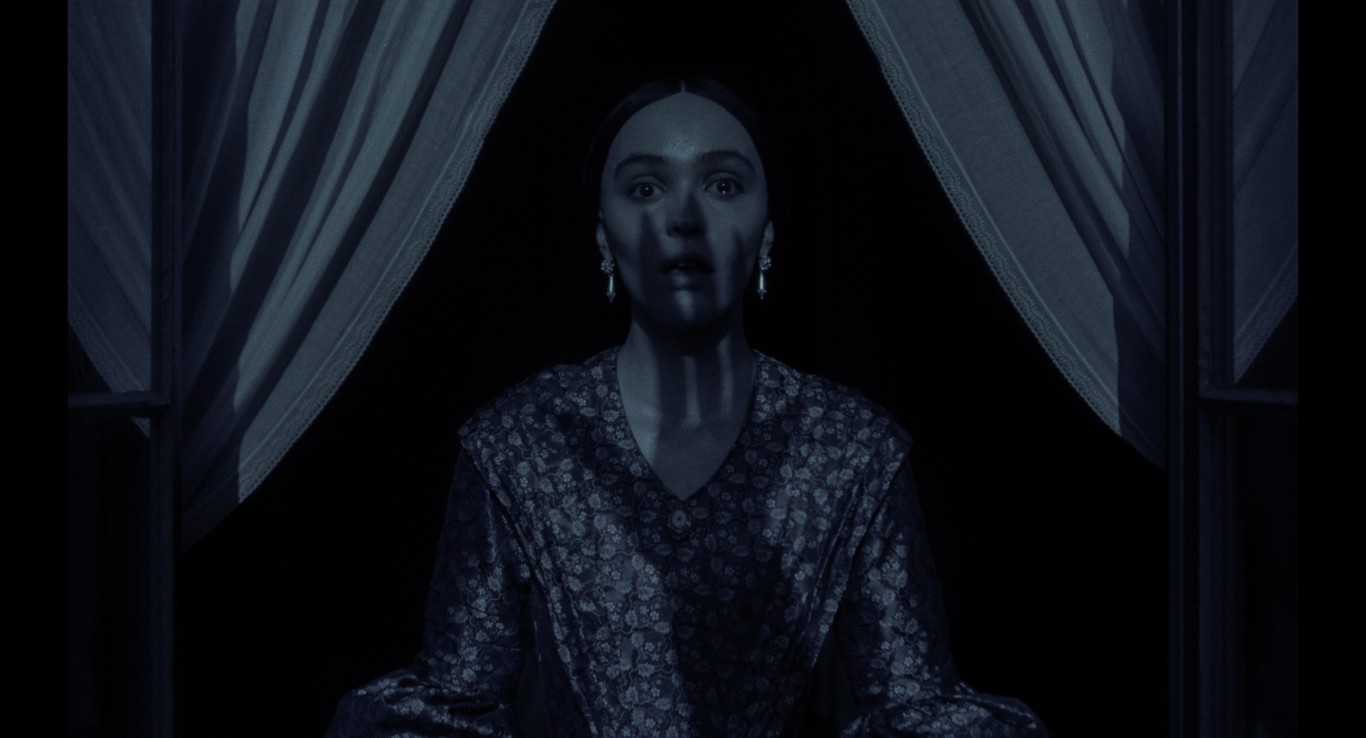

Steeped in the shadows of its lineage—not only the German Expressionist original but also Bram Stoker’s novel and the folkloric roots from whence it came—Eggers’ “Nosferatu” is also boldly distinguished by its vision of the horrific bond between vampiric Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård) and tormented Ellen Hutter (Lily-Rose Depp), the object of his carnal infatuation.

Though it mainly unfolds in 1838, in the fictional German town of Wisborg, Eggers’ film opens with a prologue, set years earlier. Desperately lonely, a young Ellen cries out from her bedroom for “a guardian angel, a spirit of comfort, a spirit of any celestial sphere, anything” to offer her companionship. Instead, Ellen inadvertently summons Orlok, whose rasping whisper beckons her outside and tempts her—writhing between pleasure and pain—to swear herself to him “ever eternally,” before violently ravaging her. Whereas previous versions of “Nosferatu” focused on her husband, Thomas Hutter (Nicholas Hoult), the lifeblood of Eggers’ adaptation is this psychic connection between Ellen and Orlok, born of her sensitivity to the spirit realm and intensified by her repressed sexual desire.

In his telling, Ellen is a victim of 19th-century society as much as the vampire, and it is only through succumbing to darkness that she can defeat it within herself. Eggers has long been fascinated by the nature of fear, and by surrender to the arcane as a form of liberation. New England folk tales “The Witch” and “The Lighthouse” followed characters in thrall to darkness, bedeviled by an enchantment in the light, and his Viking saga “The Northman” was propelled forward by a similarly primitive bloodlust.

A modern filmmaker most at home in the distant past, Eggers is known for intricate research and period detail. Even as his narratives reach back into antiquity, to that point where history gyres into legend, he seeks pungent authenticity. Recreating not only the material realms but also rituals and belief systems of olden times, Eggers proposes that the worlds of mythology and reality were once closely entwined.

So it is with his “Nosferatu,” which clothes Orlok in traditional Romanian aristocratic garb while drawing upon Balkan and Slavic vampire lore to re-envision him as a rotting corpse, and which recreates the Biedermeier furnishings and brick Gothic buildings of 1838 Germany to ground the supernatural in realism. An atmospheric triumph, the film reunites Eggers with cinematographer Jarin Blaschke, production designer Craig Lathrop, editor Louise Ford, and costume designer Linda Muir, the team that’s worked on all his films.

Eggers first announced his intention to remake “Nosferatu” 10 years ago, but his affinity for the landmark 1922 horror goes back much further. Growing up in New Hampshire, Eggers first encountered Orlok as a 9-year-old, on a VHS copy of Murnau’s “Nosferatu” made from a faded 16-millimeter print. He was so compelled by Max Schreck’s performance of the titular vampire, which felt all the more eerily authentic within the degraded version of the film he saw, that in high school, he directed a stage adaptation—later staged professionally—that was both silent and black-and-white, with music playing and actors painted monochrome. (Orlok was played, of course, by Eggers himself.)

Earlier this week, Eggers sat down to discuss the path of his long-gestating “Nosferatu,” the power of immersion in antiquated perspective, the lingering influence of Jack Clayton’s “The Innocents,” and more.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

You started working toward remaking “Nosferatu” about 10 years ago, though you have a much longer history with the Murnau. How did the project evolve over time, as you were working to bring it to the screen?

So, yes, I had originally put together this high school play of “Nosferatu,” when I was 17. That was then brought to a local theater and done more professionally, and that was extremely Expressionist—and more Expressionist than the Murnau film. I mean, the budget was meager, but it was more “Caligari”-icized.

The Murnau film, I would argue, even though the writing and acting styles are Expressionist, that it is not particularly Expressionist. Certainly, I’d say that Murnau, [producer and production designer] Albin Grau, and his collaborators were more interested in German Romanticism. If you think about it, “Dracula” had come out not that long before they made “Nosferatu,” and they probably felt that setting it in the period where “Dracula” was set would have been dated and lame. What was really cool was back in the 1830s, to them.

In doing my adaptation, I was trying to understand their impulses, and I also found it exciting to be more romantic and in the German Biedermeier period. But once I had the first draft of the script, it didn’t change a whole heck of a lot in terms of what I wanted the film to be. What’s changed is that I’m better at being a person, at being a film director, and that my collaboration with my heads of department has grown more fluid, more complex, and better. We were all better-equipped to make the movie that we’d been talking about for a long time.

In that effort to understand the original impulses of Murnau, Grau, and his collaborators, you actually wrote a novella at one point, to work through elements of what might have been on their minds—and on the minds of the story’s characters—in their respective time periods. What did that process of tracing the lineage add to your understanding of their intentions, especially with regard to their conception of the vampire?

We only have 15 minutes, so it’s too much to unpack, but one of the things that was interesting to consider was that there was sensationalist press that Albin Grau did for “Nosferatu,” talking about Serbian vampires in the war. I think he believed in the existence of psychic vampires who would come and visit victims through astral projection; I think, given his interest in the occult, there’s pretty much no question in my mind that he believed that that was real.

One of the tasks I had was synthesizing Grau’s 20th-century occultism with cult understandings of the 1830s and with the Transylvanian folklore that was my guiding principle for how Orlok was going to be, what things he was going to do, and the mythology around him. I was synthesizing a mythology that worked with all of that.

The other things that were crucial in this exploration of the novella was expanding the Ellen character, making this her story, and also the secondary or tertiary characters of the Harding family, finding a way to give them enough screen time with enough weight for you to care about their story, knowing it was going to be limited. Basically, the novella allowed me to really overwrite their characters, so that I could find a way to condense it down.

I often feel you achieve this historical immersion outside of the material, in how you reflect the psychology of your characters: customs, superstitions, belief systems. To what degree are you suppressing the influence of your more modern mind in making these films?

As much as possible. I mean, obviously, it’s impossible to completely leave yourself, but when you’re writing each character, you need to inhabit them the way an actor would, so I try my damnedest.

You care deeply about language, both in terms of linguistic realism in your films and a certain stylization through dialect. How did you approach that in this film? Of course, they’re not speaking German, but there’s Count Orlok’s dialect, but also verse speaking; Aaron Taylor-Johnson’s Friedrich Harding even quotes Shakespeare.

It takes place in Germany, which is where I dated it primarily, but I went Hammer Horror-style and had them speaking British Received Pronunciation, as well as some London Cockney for the lower-class characters. I read a lot of 19th-century novels to immerse myself in that world.

“The readiness is all,” as Harding says, was meant to be Harding reaching for a stock phrase to express himself in that situation, because he was at a loss for words. Then, of course, there are characters who speak Romanian, characters who speak Romani.

Orlok’s magical language is ancient Dacian, which is a dead language spoken by the ancestors of the ethnic Romanians. To get that, Florin Lazarescu, who is the Romanian consultant, did his interpretation of my Orlok poetry into ancient Dacian.

There are such layers contained in this question Ellen asks: “Does evil come from within us, or from beyond?” Given that “Nosferatu” is set in 1838, before Germany was unified into a nation-state, I’m curious to what degree you considered that anxiety of emerging national identity and this fear of “the Other,” in this case Eastern Europeans, within your adaptation.

[long pause] My works tend to be less intentionally politically charged, and that was also something that was not necessarily front of mind for me. I think there’s a lot of criticism about “Dracula” and Murnau’s film, about this Other from the East coming in. But that’s not what excites me about the story.

What does excite you about the story?

I think that what ultimately rose to the top, as the theme or trope that was most compelling to me, was that of the demon-lover. In “Dracula,” the book by Bram Stoker, the vampire is coming to England, seemingly, for world domination. Lucy and Mina are just convenient throats that happen to be around. But in this “Nosferatu,” he’s coming for Ellen. This love triangle that is similar to “Wuthering Heights,” the novel, was more compelling to me than any political themes.

All of your films navigate this idea of original sin, this mixture of attraction and repulsion we feel toward sex and death. What draws you to that subject matter?

It’s hard for me to be reflective about that, as in regards to my particular attraction to it. I think it’s interesting that vampires were very inspiring to me as a kid. The power of the vampire is this symbol of sex and death—and these are taboo subjects to discuss as a kid, even to understand as a kid. And yet, there’s something fascinating, compelling, and attractive about this person who holds a lot of power, who inhabits those two worlds. I was also very interested in witches as a kid, but they scared me. I didn’t want to be a witch. I was fascinated by how much they scared me, but the vampire… It seemed like I would want to be that, right?

And so you cast yourself as Orlok in the high school play.

Yeah.

The film is steeped in German Expressionist influences, including Murnau’s films outside of “Nosferatu,” like “Faust” and “Sunrise.” Where did you consciously choose to evoke those films, and how did you approach doing so with your craftspeople while interpreting them in your own cinematic language?

There was a conscious decision between myself and [cinematographer] Jarin Blaschke to not replicate any of Murnau’s shots from “Nosferatu,” and we didn’t. And then there’s “Faust” and “Sunrise” and “The Last Laugh”—you name it, I’ve just seen these films a lot.

The one shot that points to “Faust,” and also Archie Mayo’s “Svengali,” is the shot of Orlok’s hand over the city. That’s not a shot specifically from either of those films, but you can hopefully see the influence of both Satan’s wings as a plague comes in “Faust” and John Barrymore reaching out telepathically to Marian Marsh in the night in “Svengali.” There’s also one shot, [in which Hutter’s carriage nears Orlok’s castle,] that’s completely an ode to Tod Browning’s “Dracula,” [the opening shot of which depicts travelers riding in a carriage through Transylvania’s Borgo Pass.] In general, though, we’re hoping that our influences get broken down through some kind of alchemical process and become something else, even if you can smell them and are aware of them. Sometimes, we’re more successful than others.

I would also put out there that the biggest cinematic influence on the film, aside from Murnau, is Jack Clayton’s “The Innocents.” It’s also Freddie Francis, the cinematographer, and his staging in not only that film, which was obviously done with Jack Clayton, but also his films as a director.

I rewatched “The Innocents” recently and was taken aback to find it more psychologically complex and sexually charged than I’d remembered.

It’s heavy-duty. That movie often made me wonder if I was going too far with being explicit about some of the sexual content in my film, because that film obviously works so well with keeping everything in your imagination. And the Murnau film, I also feel, is quite erotically charged in its own way. And, certainly, I’ve seen TV movies of Henry James’ “The Turn of the Screw” where everything is on the surface rather than made subtextual, and it doesn’t have the same effect.

The character of Ellen is central to this adaptation of “Nosferatu,” and Lily-Rose Depp’s performance is astounding. Was there a particular moment, that you can recall, where you first knew that she was right for the role?

It was her audition, which I didn’t pull any punches with. I asked her to do the monologue where she describes the dream of death, and then I asked her to do the big scene between herself and Nicholas Hoult at the end, where she’s wearing the brown-and-white-striped dress, and with the tongue—the whole thing.

Right away?

I had to! I had to see: can you go there? Obviously, those scenes weren’t as technically precise as they were in the film, but she had the same raw and courageous ferociousness. It was clear to me then that she had it and that she was going to succeed.

“Nosferatu” is now in theaters, via Focus Features.