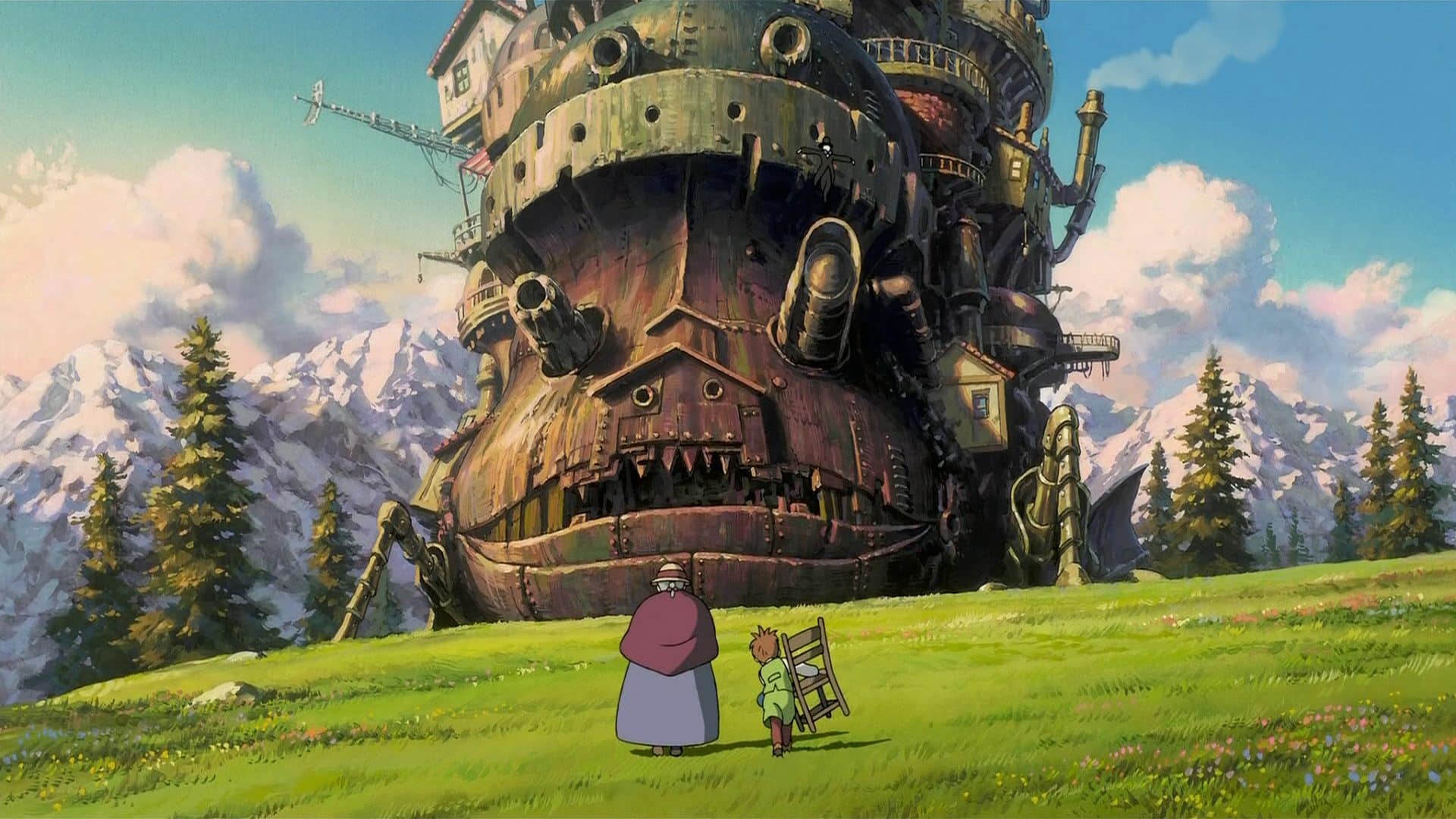

At the end of Hayao Miyazaki’s visually stunning “Howl’s Moving Castle,” the titular Howl bemoans a sudden ache in his chest. The protagonist, Sophie, succinct yet joyful, replies, “A heart’s a heavy burden.”

The poignancy of the line demonstrates Miyazaki’s ability to enchant viewers with staggering artistry and spellbinding narratives that both whisk us away to other worlds while grounding them in genuine human emotions. These characters experience all things extraordinary. They encounter selfish witchcraft and consume falling stars; they witness the transformation of a cursed prince back into a human through the power of love. “Howl,” like much of Miyazaki’s filmography, is grounded in the human element of caring for others. It is crucial to the film’s messaging and relates to Miyazaki’s tireless work. This is especially true of his late career, where visions of art, beauty, and death meld together in a cacophony of memories, visions, and dreams. “The Wind Rises,” “The Boy and the Heron,” and the latest documentary “Hayao Miyazaki and the Heron” suggest a director whose priorities have shifted. Yet between the old and the new, that line from Sophie rings true. The heart is a heavy burden, and Miyazaki seems intent on visualizing its, at times, exhaustive weight.

The value of artistry and legacy permeates throughout Miyazaki’s most recent works. “The Wind Rises,’ “The Boy and the Heron,” and the documentary all demonstrate a crucial shift in the tonality of the director’s oeuvre. His early films felt the weight of humanity, acting as cautionary tales of what could happen if protagonists could not get to the core of the rot of the world. His latest works, in comparison, offer reflection and melancholy. No longer do they possess that youthful idealism evident in his earlier films. His latest contains the knowledge that hope for the future lay in the hands of others — in younger hands whose idealism may rectify past generational trauma. It’s burdensome to care, but it’s our obligation to do so.

It’s not just that Howl is awakening to the idea that he must now feel the repercussions of his actions, but the consequences of his care. His care for Sophie and the found family surrounding him. Love is just as tremendous a weight to carry as pain or guilt. More than anything, it’s that which speaks to what becomes crucial elements in Miyazaki’s work. We witness the tolls of artistry and how our love and emotional tethers influence who we become and what we create in light of it.

In many ways, “Howl’s Moving Castle”—celebrating its 20th anniversary—feels like the perfect intersection of his old and new work. Sophie, cursed by the Witch of the Waste into a 90-year-old woman, offers the duality of being both young and old and experiences a certain enlightenment with age that empowers her. This contrasts with “The Boy and the Heron,” where the wisdom of age comes packaged with fear for the future. Sophie revels in the lack of expectations from being a young woman in a 90-year-old’s body. Meanwhile, the Granduncle, a key figure in “Heron,” experiences a great, seismic trepidation regarding the future due to all the days he’s lived.

Howl loses his tethers to humanity when transforming into a bird-like creature to interfere with both sides of the war taking place in “Howl.” This contrasts with Jiro in “The Wind Rises,” who regrets that his dream aircraft was used for war. The film itself is stunning, a visual spectacle that perfectly blend all things Miyazaki that aids in transitioning the filmmaker into his more recent outputs.

Thematic core beliefs and stylistic choices link all of his work—from environmentalism to the inevitable persistence of time, the hope found in companionship, and his interest in aviation—but his recent films act as a coda to his long career.

“The Wind Rises” and “The Boy and the Heron” are two sides of the same coin. Cynical vs esoteric. Intellectual vs emotional. Two very different films trying to grapple with similar ideologies about what we leave behind. Both represent the culmination of career highs and lows, belief systems, and artistry. “The Wind Rises” deals with what our passions drive us towards and, ultimately, what our creations leave behind. It’s a rumination on how a person’s dreams can pave a path of wreckage or salvation.

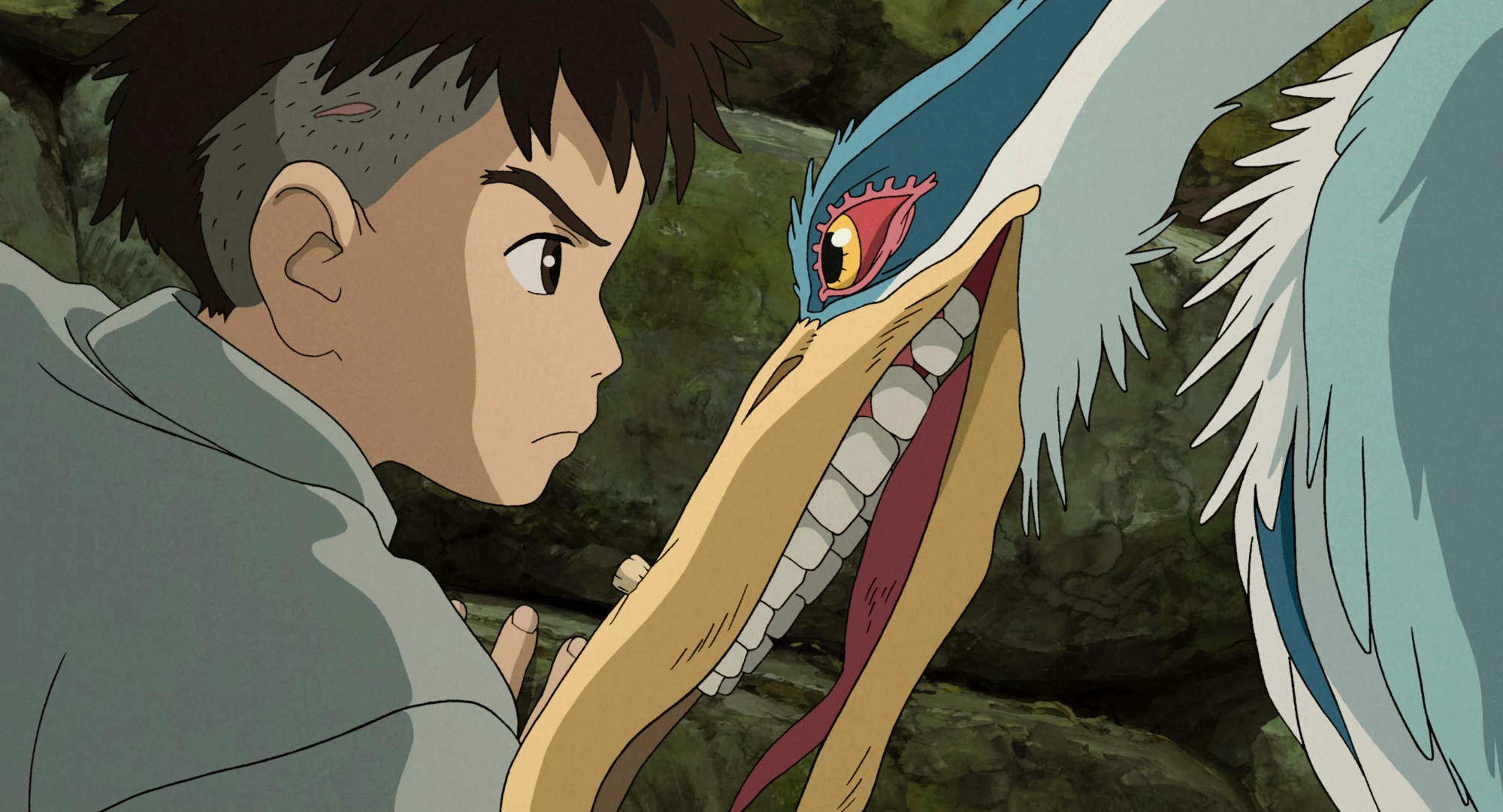

“The Boy and the Heron,” arguably his most personal, acts as an ode to his current regrets and meditation on life, culminating in astonishing catharsis. Grief seeps into every crevice of “The Boy and the Heron” without being particularly mournful. His heart, here, is in unmistakable loss. Loss of time, of a loved one, and the potential loss of innocence through corruption. From the moment Mahito loses his mother, running through a town terrorized by panicked cries, he’s lost part of his innocence. His heart is heavier now as he traverses an ever-changing world.

Perhaps the best encapsulation of his current state of mind is through lifting the veil in “Hayao Miyazaki and the Heron,” which details his long and tumultuous experience in bringing the 2023 film to life. It’s here, too, where we understand the aches that announce themselves, present and wounded, in the film. In “Heron,” Mahito mourns his mother. Through the film, Miyazaki mourns friends and rivals, those who continue to disappear from his life, leaving him behind.

His reminiscing is largely spent talking about fellow filmmaker Isao Takahata (“Grave of Fireflies,” “The Tale of the Princess Kaguya”) and Studio Ghibli key animator and color designer Michiyo Yasuda — the latter of whom pushed him to direct “Heron.”

He grapples with grief while contending with his age; his daily walks intersect with footage of a nearby daycare where kids run and play. The messaging is clear, made more so by his longtime producer, who asks, “How can he be happy with the years he has left.”

Through creation, it would seem. In this case, grief propels art. “If we don’t create, there’s nothing,” Miyazaki says. And this keen desire to never rest makes the love and loss he carries so evident in his work. It’s yet another instance of the cumbersome nature of matters of the heart. We carry it, and it only grows heavier as we age. We persevere, unable to do anything but.

Perhaps that’s why “Look Back,” the recently released animated film directed by Kiyotaka Oshiyama and based on the manga from Tatsuki Fujimoto, hits such a chord when thinking about Miyazaki and legacy. “Look Back” also deals with the world of artists and the forged path ahead of them as two young girls face the endless hurdles of being creative in an ever-changing field. As we watch the protagonist, Fujino, hover over her desk day after day as she strives for perfection, it cuts a strikingly similar image to “Heron.” In the latter, we see Mahito sit over his desk as composer Joe Hisaishi’s expressive “Ask Me Why” plays for a second time, as he finds a book left by his late mother for an older Mahito titled “How do you live?”

How do you live? Hunched over a desk. How do you live? Through our connections, our peers, and loved ones who champion and challenge us. How do you live? We live through the infinite vitality of art. So much of Miyazaki’s latter work deals with how we ruminate over life’s hurdles and the passage of time, most notably what binds us to the past and helps us grow toward the future. Miyazaki’s films process how we are responsible for creating the universe we wish to live in and seeking a life without malice or greed. And yet the tone of “Princess Mononoke” and “Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind” is stark in contrast with “The Wind Rises” and “The Boy and the Heron.” Perhaps because the latter two are twinged with the heaviness of loss.

In many ways, “Howl’s Moving Castle” is Miyazaki at his most mainstream. And yet, 20 years later, it’s easy to see how this was a turning point for him in his career. While he’s focused on older protagonists in the past — most notably, “Porco Rosso,” “Howl,” in turn, feels like a strong pivot of what stories he’s trying to tell with a distinctive perspective shift. Possessing such boundless limitations, “Howl” imbues such spark and light in a war-torn world. But it’s that line that ties the film and Miyazaki’s filmography all together.

Of course, many lines from his films speak to similar themes. But this sense of urgency lodged in your chest, the necessity of the heart and how we wield it — for good, for others who cannot, in the pursuit of creativity — is the throughline of his most recent works, and they’re all the more potent because of it.

Between the kingdoms of dreams in “The Wind Rises” and the bridge of life, death, and madness in “The Boy and the Heron,” Miyazaki exposes his beating and exhausted heart. The sheer grandiosity of his animation belies a simple truth — if we’re lucky, we all become stories for someone else to share, to mourn. What carries us through is the art born from the heaviness we bear.