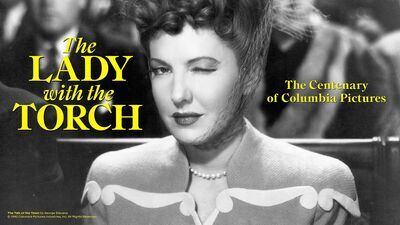

The hardest part about attending a film festival strictly as a critic, is knowing you have little chance of seeing the wealth of retrospective titles programmed. It’s just so difficult to divide your time away from the newer titles, mostly because, quite frankly, those pay the bills. Often you just hope your local repertory movie theater will bring what you missed to their screens. But when Locarno Film Festival announced its celebratory retrospective series “The Lady With the Torch,” its programme of Columbia Pictures films (1929-1959), marking the hundredth anniversary of the studio—I just knew I couldn’t pass it up. Rather than tooling my schedule for World Premieres, I made these classics and rarities my priority.

The series was a marathon event — my lone complaint is that you couldn’t have come close to seeing all 44 films screened unless they made up the entirety of your schedule — and I was able to view 13 of them, most of them as first time-watches. With the exception of “Gun Fury,” which played in 3D (more on that in a bit), every film screened at the GranRex Cinema, and was accompanied by introductions from a bevy of film critics and historians, like Farran Smith Nehme, Pamela Hutchinson, Christina Newland, and Ehsan Khoshbakht. These writers—along with Jonathan Rosenbaum, Chris Fujiwara, Imogen Sara Smith, Elana Lazic, Christopher Small, and more, also contributed to the anthology of essays accompanying the series. Edited by Khoshbakht, The Lady With the Torch is a wealth of history backgrounding the building of the studio: figures like controversial studio co-founder Harry Cohn, and directors like Charles Vidor, Hugo Haas, William Castle, Howard Hawks and more are analyzed. As is the studio’s unique takes on melodramas, noirs, women’s pictures, screwballs, westerns, war flicks, and social justice works.

The picture that is painted by historian Matthew H. Bernstein in his chapter, is of a Poverty Row studio operating on the margins, which quickly and efficiently churned out B-movies to fuel its later swings at A-pictures, that would, through unlikely circumstances, by the 1950s eventually allow the studio to graduate to producing big budget epics. “No one in the industry, including those three [Columbia Pictures founders Jack and Harry Cohn and Joe Brandt], could have predicted the studio’s longevity… Against all odds, and despite its inauspicious beginnings, by the end of the classical era, Columbia had risen to a place of profitability and prestige,” notes Bernstein. What The Lady With The Torch also makes clear is how Columbia fostered talent, allowing directors and stars to ply their trade in B-movies before handing them bigger opportunities to create memorable work that would form the backbone of the studio’s legacy.

I am thrilled to have caught as many films as I did — many of them screened on 35mm — with each presenter bringing an incredible trove of knowledge that primed audiences to view these wonderful treasures. Below are the 13 films I managed to catch from this wide-ranging series.

“Vanity Street” (1932)

Like many of the directors on this list, Nick Grinde was a B-movie savant. During his career he bounced from studio to studio. But he found his warmest home at Columbia, where he directed ten films. “Vanity Street” wasn’t his first collaboration with the studio (the Barbara Stanwyck starring “Shopworm” holds that distinction). But the Pre-Code is emblematic of the quick-hitting, efficiently crafted works that would be a trademark to his career.

While Charles Bickford’s granite face doesn’t make for a natural romantic lead, “Vanity Street” leans into that fact by casting him as a brusque, sympathetic detective who scoops the starving, homeless Jeanie Gregg (Helen Chandler) off the street — rather than throwing her in jail for throwing a brick through a diner window — and gives her job in the Follies before later bailing her out of a murder rap. Bickford is quite touching as the detective who doesn’t believe he deserves an ebullient Chandler’s love. In the background of the will-they-won’t-they affair is also a gripping, salacious picture referencing sex working and the perilous place aging women hold in showbusiness — making for a slick melodrama.

“Twentieth Century” (1934)

If you asked someone to describe the prototypical screwball comedy, chances they’d either evoke “It Happened One Night” or “Twentieth Century.” While the latter was produced to capitalize off the success of the former, its chronological placement doesn’t make it any less of a scorching picture. Its success stems from its dream team lineup: the legendary Howard Hawks directs, the prolific Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur wrote it, cinematographer Joseph August lensed and editor Gene Havlick cut it (both worked on “Vanity Street”), and John Barrymore in one of his last great performances combined forces with a transcendent Carole Lombard to star.

In this marriage-remarriage screwball, Barrymore is the self-absorbed playwright Oscar Jaffe, who is so confident of his star-making prowess, he casts the inexperienced Mildred Plotka (Lombard) in the starring role of his latest production — renaming her Lily Garland — and eventually marrying her. Years later, not only is Garland a star. She is finished with the verbally abusive, toxically manipulative and unconscionably jealous Jaffe. She leaves him for a career in Hollywood. Their relationship seems over until they find themselves on the same train, where a desperate Jaffe attempts to re-sign Garland for one last production. There aren’t enough adjectives to fully commend Barrymore and Lombard for their peerless work, here. But they’re so effortlessly brilliant together as both verbal and physical comedians that the film’s final note somehow feels fitting despite its obvious horror.

“If You Could Only Cook” (1935)

Another marriage-remarriage screwball, William A. Seiter’s “If You Could Only Cook” has a wacky premise. Jim Buchanan (Herbert Marshall), the owner of Buchanan Motor Company, is disillusioned with the quick profit mentality of his board and the soulless love of his fiance Evelyn Fletcher (Frieda Inescort). On a park bench he meets an unemployed Joan Hawthorne (Jean Arthur) combing the want-ads for a job. When she comes across a job asking for a cook and a butler, she, mistaking Buchanan for another job-seeker, proposes that they pose as a married couple and apply for the job. They somehow get the positions working for mobster Mike Rossini (Leo Carrillo), a foodie with a specific palette for garlic. The subterfuge doesn’t make much sense — after all, no one recognizes the area’s largest car manufacturer until his picture pops up in the paper — but the film’s casting is so spot on, especially the spitfire Arthur, alongside the hilarious Lionel Stander as Rossini’s lieutenant, that the ensuing hijinks still power the threadbare story without much let up.

“Let Us Live” (1939)

Anytime I see Henry Fonda on screen, it’s a jarring experience. Not because he isn’t an incredible actor. I’m just awestruck by how his naturalistic style is so far ahead of his contemporaries. While 1939 was a banner year for Fonda — featuring starring roles in “Jesse James,” “Drums Along the Mohawk,” and “Young Mr. Lincoln” — its director John Brahm’s “Let Us Live” of the same year that gives a full accounting of Fonda’s incredible range.

He begins the film in the image of his soft-spoken everyman persona as Brick Tennant, an optimistic cab driver preparing to wed Mary Roberts (Maureen O’Sullivan). His world is turned upside down, however, when an old friend — Joe Linden (Alan Baxter) — arrives looking for a job and a place to crash. Brick hires Joe, loaning him an old cab that Joe, with a ruthless gang, uses to stage several robberies. The thefts lead back to Brick, putting him on death row with Joe while Mary teams with Lieutenant Everett (Ralph Bellamy) to clear Brick’s name. This film takes a hard look at capital punishment and critiques the inequities of the justice system. And while the actual investigation is frustrating, that’s sorta the point: The system is so intent on finding a culprit, it haphazardly points the finger at Joe. The hopelessness of Brick’s plight causes the once genial man to change. By the end, Fonda is a completely different person — draped in an uncontrollable rage that foreshadows the later darkened turn he’d take in “Once Upon a Time in the West.”

“Girls Under 21” (1940)

A fascinating entry in the “women’s picture” subgenre, Max Nosseck’s “Girls Under 21” is a morality play that’s simple enough. Frances White Ryan (Rochelle Hudson) returns to her downtrodden neighborhood following a prison sentence in connection with her gangster husband Smiley Ryan (Bruce Cabot). Frances wants to go straight, but the older, conservative women in her community won’t forget her past. Meanwhile, Frances’ sister Jennie (Tina Thayer), along with Jennie’s young cohort, want Frances’ fine clothes and lifestyle. They decide on a life of crime, despite their idealistic teacher Johnny Crane (Paul Kelly) believing they’re capable of more. The girls’ criminal ways eventually lead to tragedy, in a scene so shocking in its violence, it caused the entire theater to audibly gasp. Nosseck’s picture is more didactic than you’d like, and features some canned performances — but it is a compact, nifty film nonetheless.

“Under Age” (1941)

While “Girls Under 21” might be a tad too ‘afterschool special’ to be hard hitting, Edward Dmytryk’s “Under Age” is so in your face I almost mistook it for a Pre-Code. Dmytryk’s arresting blend of social issues and exploitation — a line he would jump back and forth over throughout his career, particularly with “The Sniper” (1952) — pushes this film to the limits of the censors. Another “women’s picture,” it supposes an issue afflicting America’s highways and byways: roadside motels using young women to lure male drivers for a good time. Sisters Jane (Nan Grey) and Edie Baird (Mary Anderson) are hired by one such chain owned by Mrs. Burke (Leona Maricle) following their release from prison. While the older, responsible Jane catches the eye of jewelry heir Rocky Stone (Tom Neal), her younger sister Edie — drunk off the money, fine clothes, and attention afforded by her salacious trade — falls for Mrs. Burke’s violent right-hand-man Tap Manson (Alan Baxter). Surprisingly the film does more than allude to these women as prostitutes, and features an incredibly gruesome murder that left my mouth agape. Its theme of collective empowerment is stirring; its use of shadows is evocative; its awareness of the body to enrapture is startling. This film feels like one of the real discoveries from the series.

“None Shall Escape” (1944)

Similar to many directors of his era, Andre de Toth sorta did everything: westerns, horror, war pictures, and noir. “None Shall Escape,” one of his early films after emigrating to America from Hungary during World War II, is a time-bending work. “As Jean-Luc Godard’s ‘Alphaville’ would do two decades later,” notes critic Jonanthan Rosenbaum in his chapter for The Lady With the Torch “‘None Shall Escape’ — its title derived from a Franklin Roosevelt speech about Nazi crimes — plants a sharp look at the recent past inside the recent (or soon to be materialized) future. One might even say it mixes tenses in order to address the present.”

Toth’s film imagines and predicts a war tribunal, not unlike the later Nuremberg Trials, where Nazi war criminal Wilhelm Grimm (Alexander Knox) stands accused of murder. The film flashes back through witness testimony provided by Grimm’s former fiance Marja Pacierkowski (Marsha Hunt), her uncle Father Warecki (Henry Travers), and Grimm’s brother (Erik Rolf) to chronicle Grimm’s descent from school master to antisemite. The trial itself is riveting, even if the construction is obvious. But it’s a speech conducted by Rabbi David Levin (Richard Hale) as Jews are being forced into cattle cars — which speaks upon the need for the oppressed people of the world to unite — that is equally harrowing and urgent in a moment where genocide in Gaza is presently occurring.

“Mysterious Intruder” (1946)

As a producer, William Castle is probably best known for “The Lady from Shanghai” and “Rosemary’s Baby.” As a director, he made his name self-releasing wildly successful B-horror films like “House on Haunted Hill.” But Castle first broke out when Harry Cohn assigned him to direct “The Whistler” (1944), an adaptation of the same-titled radio serial. It became exceptionally popular, spawning eight total films in the series. “Mysterious Intruder” is the fifth, and follows the unscrupulous private eye Earl C. Conrad (Richard Dix) as he works to find the long missing Elora Lund (Pamela Blake) for the aged antique salesman Edward Stillwell (Paul E. Burns) — who claims to possess two rare wax cylinders worth hundreds of thousands of dollars belonging to Lund. The dollar signs not only interest Conrad, they cause a couple of mysterious murderers to pick up the scent too. Like the rest of the series, “Mysterious Intruder” keeps its radioplay elements, cutting to the shadow of the raspy-voiced narrator the Whistler (Otto Forrest) to keep viewers abreast of the film’s psychological underpinnings. This is a sharp-tongued, rough around the edges noir that ends on a surprising yet satisfying final scene.

“The Killer That Stalked New York” (1950)

Let’s just say after COVID — I use the word “after” very loosely — Earl McEvoy’s pandemic thriller “The Killer That Stalked New York” hits a bit differently. Based on a 1948 Cosmopolitan article by Milton Lehman, it follows Sheila Bennet (Evelyn Keyes) — who has recently returned from Cuba, where she illicitly shipped stolen diamonds in the mail to her no-good husband Matt Crane (Charles Korvin). When she returns, not only is she being trailed by a Treasury agent, she also finds Matt in a relationship with her younger sister Francie (Lola Albright). To make matters worse, she is gravely ill. Sheila seeks help from Dr. Ben Wood (William Bishop). At his office she meets a young girl, who, with through her contact with Sheila, contracts smallpox. The disease begins to spread across New York City, spurring Ben and the Department of Health to search for patient zero: Sheila. This is a pro-vaccine film, one that captures an appropriately shaken government ready to spring into action to prevent further unnecessary death. While the film is a socially conscious work, as Khoshbakht observes in his essay in The Lady With The Torch, it also represents how Columbia produced directors and stars. Its director McEvoy moved up from second unit work to helm this picture, one of his few directorial efforts.

“Pickup” (1951)

I’ve slowly been working my way through Hugo Haas’ directed works, previously watching “Bait,” “One Girl’s Confession,” and “Hold Back Tomorrow.” So I was immediately keen to catch “Pickup,” his directorial debut in America (he previously enjoyed a sizable film career in the Czech Republic). Along with directing, Haas self-produced, co-wrote with Arnold Phillips, and starred in the picture as Jan Horak — a tender-hearted railroad dispatcher who attends a carnival looking for a dog but comes home married to the gold digging Betty (Beverly Michaels). Jan is too sweet of a man to see that Betty, who’s miserable living in the middle of nowhere at his depot, not only doesn’t love him, but is smitten by his young assistant Steve (Allan Nixon). When Jan suddenly goes deaf, Betty sees the disability as her chance to steal his money and bolt. Her plan goes awry, however, when Jan, after he miraculously regains his hearing, pretends to be deaf. “Pickup” features an impressive sound design, relying on high-pitch squeals to unmoor the viewer, and excels at a psychological seediness that is lean and mean yet filled with immense heart and warmth.

“The Glass Wall” (1953)

Playing at Locarno for the first time since it won the Golden Leopard in 1951, Maxwell Shane’s “The Glass Wall” is a vexing tale that puts America’s broken immigration system under the spotlight. Peter Kuban (Vittorio Gassman) is a Holocaust survivor who has stowed away on a ship heading to New York City. Once in America, he is detained, where he tells the story of how he helped save an American G.I. during the war. Unfortunately, he only knows the soldier’s first name — Tom (Jerry Paris) — and that he’s a clarinet player living in New York. None of those details are enough to guarantee his place in America; he needs to find the real Tom within 24 hours or he’ll be deported. Peter breaks out of custody toward Time Square to search for Tom, where, along the way, he meets helpful souls like Maggie Summers (Gloria Grahame) and a burlesque dancer named Nancy (Robin Raymond).

Gassman, an Italian actor playing Hungarian, is simply tremendous as Peter, demonstrating clear desperation yet a hopeful view of the world, despite his wretched circumstances, which gives this picture its moral compass. If a “model migrant,” in all the loaded connotations of the phrase, cannot hope to gain entry into America, then who can? That kind of question, which “The Glass Wall” raises, is one we’re still grappling with as many decry those who are not entering the country “the right way” without fully considering what a distasteful phrase — the years-long obstacles and boundaries thrown up at migrants — like that could possibly to mean those most distressed.

“Gun Fury” (1953)

As mentioned before, every film in the series, at least the ones I watched, screened at the GranRex Cinema. All of them except “Gun Fury,” a 3D western directed by the great Raoul Walsh. In the reconstructionist narrative, Rock Hudson plays Ben Warren, a pacifist with only two dreams on his mind: Marrying Jennifer Ballard (Donna Reed) and living far away from the troubles of the world on his massive ranch. Those dreams are shattered when Frank Slayton (Philip Carey), an outlaw haunted by the Lost Cause, robs a carriage carrying gold, shoots Ben and kidnaps Jennifer. When Ben awakens, he teams with Slayton’s former partner Jess (Leo Gordon) and with Johash (Pat Hogan) — an Indigenous man seeking revenge against Slayton — to hunt down the outlaw. Though the 3D in “Gun Fury” is mostly rudimentary, involving characters throwing objects at the lens, such as a loaf of bread, it’s still enrapturing to watch Walsh’s unparalleled sense of how to frame these vast landscapes and the way he captures the film’s immersive chases (at one point, we get a thrilling POV a shot from the driver of a wagon, as though we’re the ones holding the reins).

“The Last Frontier” (1955)

I am admittedly not a fan of Victor Mature. I just find his lackadaisical onscreen persona grating; I can never tell if he actually wants to be whatever movie he’s acting in. Nevertheless, I adore Anthony Mann — especially his long collaboration with James Stewart. And while Mature brings an unpredictable sense of intensity as the crude Jed Cooper — who along with fellow fur trappers Gus (James Whitmore) and Mungo (Pat Hogan) are enlisted by Captain Glenn Riordan (Guy Madison) to track an Indigenous chief named Red Cloud (Manuel Dondé) — I can’t help but feel he’s miscast here.

That doesn’t mean there aren’t fascinating elements to “The Last Frontier.” For a time it thrives as an anti-war and anti-military picture. Robert Preston appears as a General Custer-like figure, the bloodthirsty Colonel Frank Marston, whose wife Corinna (Anne Bancroft) is not only incredulous of her husband’s tactics but is also the apple of Jed’s eye. Preston provides the narrative with an easy villain to root against, one that embodies the rotten core of America’s Manifest Destiny. Jed’s desire to wear an blue army jacket is also nearly stamped out in a cathartic breakdown by Mature that demonstrates the emotional depths that always lurked underneath his stoic exterior but was rarely seen in his noir work. “The Last Frontier,” unfortunately, undoes much of that great, radical work by returning to normalcy and ultimately becoming the thing it so fervently seemed to hate — a blindly patriotic picture.

The hardest part about attending a film festival strictly as a critic, is knowing you have little chance of seeing the wealth of retrospective titles programmed. It’s just so difficult to divide your time away from the newer titles, mostly because, quite frankly, those pay the bills. Often you just hope your local repertory movie theater will bring what you missed to their screens. But when Locarno Film Festival announced its celebratory retrospective series “The Lady With the Torch,” its programme of Columbia Pictures films (1929-1959), marking the hundredth anniversary of the studio—I just knew I couldn’t pass it up. Rather than tooling my schedule for World Premieres, I made these classics and rarities my priority.

The series was a marathon event — my lone complaint is that you couldn’t have come close to seeing all 44 films screened unless they made up the entirety of your schedule — and I was able to view 13 of them, most of them as first time-watches. With the exception of “Gun Fury,” which played in 3D (more on that in a bit), every film screened at the GranRex Cinema, and was accompanied by introductions from a bevy of film critics and historians, like Farran Smith Nehme, Pamela Hutchinson, Christina Newland, and Ehsan Khoshbakht. These writers—along with Jonathan Rosenbaum, Chris Fujiwara, Imogen Sara Smith, Elana Lazic, Christopher Small, and more, also contributed to the anthology of essays accompanying the series. Edited by Khoshbakht, The Lady With the Torch is a wealth of history backgrounding the building of the studio: figures like controversial studio co-founder Harry Cohn, and directors like Charles Vidor, Hugo Haas, William Castle, Howard Hawks and more are analyzed. As is the studio’s unique takes on melodramas, noirs, women’s pictures, screwballs, westerns, war flicks, and social justice works.

The picture that is painted by historian Matthew H. Bernstein in his chapter, is of a Poverty Row studio operating on the margins, which quickly and efficiently churned out B-movies to fuel its later swings at A-pictures, that would, through unlikely circumstances, by the 1950s eventually allow the studio to graduate to producing big budget epics. “No one in the industry, including those three [Columbia Pictures founders Jack and Harry Cohn and Joe Brandt], could have predicted the studio’s longevity… Against all odds, and despite its inauspicious beginnings, by the end of the classical era, Columbia had risen to a place of profitability and prestige,” notes Bernstein. What The Lady With The Torch also makes clear is how Columbia fostered talent, allowing directors and stars to ply their trade in B-movies before handing them bigger opportunities to create memorable work that would form the backbone of the studio’s legacy.

I am thrilled to have caught as many films as I did — many of them screened on 35mm — with each presenter bringing an incredible trove of knowledge that primed audiences to view these wonderful treasures. Below are the 13 films I managed to catch from this wide-ranging series.

“Vanity Street” (1932)

Like many of the directors on this list, Nick Grinde was a B-movie savant. During his career he bounced from studio to studio. But he found his warmest home at Columbia, where he directed ten films. “Vanity Street” wasn’t his first collaboration with the studio (the Barbara Stanwyck starring “Shopworm” holds that distinction). But the Pre-Code is emblematic of the quick-hitting, efficiently crafted works that would be a trademark to his career.

While Charles Bickford’s granite face doesn’t make for a natural romantic lead, “Vanity Street” leans into that fact by casting him as a brusque, sympathetic detective who scoops the starving, homeless Jeanie Gregg (Helen Chandler) off the street — rather than throwing her in jail for throwing a brick through a diner window — and gives her job in the Follies before later bailing her out of a murder rap. Bickford is quite touching as the detective who doesn’t believe he deserves an ebullient Chandler’s love. In the background of the will-they-won’t-they affair is also a gripping, salacious picture referencing sex working and the perilous place aging women hold in showbusiness — making for a slick melodrama.

“Twentieth Century” (1934)

If you asked someone to describe the prototypical screwball comedy, chances they’d either evoke “It Happened One Night” or “Twentieth Century.” While the latter was produced to capitalize off the success of the former, its chronological placement doesn’t make it any less of a scorching picture. Its success stems from its dream team lineup: the legendary Howard Hawks directs, the prolific Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur wrote it, cinematographer Joseph August lensed and editor Gene Havlick cut it (both worked on “Vanity Street”), and John Barrymore in one of his last great performances combined forces with a transcendent Carole Lombard to star.

In this marriage-remarriage screwball, Barrymore is the self-absorbed playwright Oscar Jaffe, who is so confident of his star-making prowess, he casts the inexperienced Mildred Plotka (Lombard) in the starring role of his latest production — renaming her Lily Garland — and eventually marrying her. Years later, not only is Garland a star. She is finished with the verbally abusive, toxically manipulative and unconscionably jealous Jaffe. She leaves him for a career in Hollywood. Their relationship seems over until they find themselves on the same train, where a desperate Jaffe attempts to re-sign Garland for one last production. There aren’t enough adjectives to fully commend Barrymore and Lombard for their peerless work, here. But they’re so effortlessly brilliant together as both verbal and physical comedians that the film’s final note somehow feels fitting despite its obvious horror.

“If You Could Only Cook” (1935)

Another marriage-remarriage screwball, William A. Seiter’s “If You Could Only Cook” has a wacky premise. Jim Buchanan (Herbert Marshall), the owner of Buchanan Motor Company, is disillusioned with the quick profit mentality of his board and the soulless love of his fiance Evelyn Fletcher (Frieda Inescort). On a park bench he meets an unemployed Joan Hawthorne (Jean Arthur) combing the want-ads for a job. When she comes across a job asking for a cook and a butler, she, mistaking Buchanan for another job-seeker, proposes that they pose as a married couple and apply for the job. They somehow get the positions working for mobster Mike Rossini (Leo Carrillo), a foodie with a specific palette for garlic. The subterfuge doesn’t make much sense — after all, no one recognizes the area’s largest car manufacturer until his picture pops up in the paper — but the film’s casting is so spot on, especially the spitfire Arthur, alongside the hilarious Lionel Stander as Rossini’s lieutenant, that the ensuing hijinks still power the threadbare story without much let up.

“Let Us Live” (1939)

Anytime I see Henry Fonda on screen, it’s a jarring experience. Not because he isn’t an incredible actor. I’m just awestruck by how his naturalistic style is so far ahead of his contemporaries. While 1939 was a banner year for Fonda — featuring starring roles in “Jesse James,” “Drums Along the Mohawk,” and “Young Mr. Lincoln” — its director John Brahm’s “Let Us Live” of the same year that gives a full accounting of Fonda’s incredible range.

He begins the film in the image of his soft-spoken everyman persona as Brick Tennant, an optimistic cab driver preparing to wed Mary Roberts (Maureen O’Sullivan). His world is turned upside down, however, when an old friend — Joe Linden (Alan Baxter) — arrives looking for a job and a place to crash. Brick hires Joe, loaning him an old cab that Joe, with a ruthless gang, uses to stage several robberies. The thefts lead back to Brick, putting him on death row with Joe while Mary teams with Lieutenant Everett (Ralph Bellamy) to clear Brick’s name. This film takes a hard look at capital punishment and critiques the inequities of the justice system. And while the actual investigation is frustrating, that’s sorta the point: The system is so intent on finding a culprit, it haphazardly points the finger at Joe. The hopelessness of Brick’s plight causes the once genial man to change. By the end, Fonda is a completely different person — draped in an uncontrollable rage that foreshadows the later darkened turn he’d take in “Once Upon a Time in the West.”

“Girls Under 21” (1940)

A fascinating entry in the “women’s picture” subgenre, Max Nosseck’s “Girls Under 21” is a morality play that’s simple enough. Frances White Ryan (Rochelle Hudson) returns to her downtrodden neighborhood following a prison sentence in connection with her gangster husband Smiley Ryan (Bruce Cabot). Frances wants to go straight, but the older, conservative women in her community won’t forget her past. Meanwhile, Frances’ sister Jennie (Tina Thayer), along with Jennie’s young cohort, want Frances’ fine clothes and lifestyle. They decide on a life of crime, despite their idealistic teacher Johnny Crane (Paul Kelly) believing they’re capable of more. The girls’ criminal ways eventually lead to tragedy, in a scene so shocking in its violence, it caused the entire theater to audibly gasp. Nosseck’s picture is more didactic than you’d like, and features some canned performances — but it is a compact, nifty film nonetheless.

“Under Age” (1941)

While “Girls Under 21” might be a tad too ‘afterschool special’ to be hard hitting, Edward Dmytryk’s “Under Age” is so in your face I almost mistook it for a Pre-Code. Dmytryk’s arresting blend of social issues and exploitation — a line he would jump back and forth over throughout his career, particularly with “The Sniper” (1952) — pushes this film to the limits of the censors. Another “women’s picture,” it supposes an issue afflicting America’s highways and byways: roadside motels using young women to lure male drivers for a good time. Sisters Jane (Nan Grey) and Edie Baird (Mary Anderson) are hired by one such chain owned by Mrs. Burke (Leona Maricle) following their release from prison. While the older, responsible Jane catches the eye of jewelry heir Rocky Stone (Tom Neal), her younger sister Edie — drunk off the money, fine clothes, and attention afforded by her salacious trade — falls for Mrs. Burke’s violent right-hand-man Tap Manson (Alan Baxter). Surprisingly the film does more than allude to these women as prostitutes, and features an incredibly gruesome murder that left my mouth agape. Its theme of collective empowerment is stirring; its use of shadows is evocative; its awareness of the body to enrapture is startling. This film feels like one of the real discoveries from the series.

“None Shall Escape” (1944)

Similar to many directors of his era, Andre de Toth sorta did everything: westerns, horror, war pictures, and noir. “None Shall Escape,” one of his early films after emigrating to America from Hungary during World War II, is a time-bending work. “As Jean-Luc Godard’s ‘Alphaville’ would do two decades later,” notes critic Jonanthan Rosenbaum in his chapter for The Lady With the Torch “‘None Shall Escape’ — its title derived from a Franklin Roosevelt speech about Nazi crimes — plants a sharp look at the recent past inside the recent (or soon to be materialized) future. One might even say it mixes tenses in order to address the present.”

Toth’s film imagines and predicts a war tribunal, not unlike the later Nuremberg Trials, where Nazi war criminal Wilhelm Grimm (Alexander Knox) stands accused of murder. The film flashes back through witness testimony provided by Grimm’s former fiance Marja Pacierkowski (Marsha Hunt), her uncle Father Warecki (Henry Travers), and Grimm’s brother (Erik Rolf) to chronicle Grimm’s descent from school master to antisemite. The trial itself is riveting, even if the construction is obvious. But it’s a speech conducted by Rabbi David Levin (Richard Hale) as Jews are being forced into cattle cars — which speaks upon the need for the oppressed people of the world to unite — that is equally harrowing and urgent in a moment where genocide in Gaza is presently occurring.

“Mysterious Intruder” (1946)

As a producer, William Castle is probably best known for “The Lady from Shanghai” and “Rosemary’s Baby.” As a director, he made his name self-releasing wildly successful B-horror films like “House on Haunted Hill.” But Castle first broke out when Harry Cohn assigned him to direct “The Whistler” (1944), an adaptation of the same-titled radio serial. It became exceptionally popular, spawning eight total films in the series. “Mysterious Intruder” is the fifth, and follows the unscrupulous private eye Earl C. Conrad (Richard Dix) as he works to find the long missing Elora Lund (Pamela Blake) for the aged antique salesman Edward Stillwell (Paul E. Burns) — who claims to possess two rare wax cylinders worth hundreds of thousands of dollars belonging to Lund. The dollar signs not only interest Conrad, they cause a couple of mysterious murderers to pick up the scent too. Like the rest of the series, “Mysterious Intruder” keeps its radioplay elements, cutting to the shadow of the raspy-voiced narrator the Whistler (Otto Forrest) to keep viewers abreast of the film’s psychological underpinnings. This is a sharp-tongued, rough around the edges noir that ends on a surprising yet satisfying final scene.

“The Killer That Stalked New York” (1950)

Let’s just say after COVID — I use the word “after” very loosely — Earl McEvoy’s pandemic thriller “The Killer That Stalked New York” hits a bit differently. Based on a 1948 Cosmopolitan article by Milton Lehman, it follows Sheila Bennet (Evelyn Keyes) — who has recently returned from Cuba, where she illicitly shipped stolen diamonds in the mail to her no-good husband Matt Crane (Charles Korvin). When she returns, not only is she being trailed by a Treasury agent, she also finds Matt in a relationship with her younger sister Francie (Lola Albright). To make matters worse, she is gravely ill. Sheila seeks help from Dr. Ben Wood (William Bishop). At his office she meets a young girl, who, with through her contact with Sheila, contracts smallpox. The disease begins to spread across New York City, spurring Ben and the Department of Health to search for patient zero: Sheila. This is a pro-vaccine film, one that captures an appropriately shaken government ready to spring into action to prevent further unnecessary death. While the film is a socially conscious work, as Khoshbakht observes in his essay in The Lady With The Torch, it also represents how Columbia produced directors and stars. Its director McEvoy moved up from second unit work to helm this picture, one of his few directorial efforts.

“Pickup” (1951)

I’ve slowly been working my way through Hugo Haas’ directed works, previously watching “Bait,” “One Girl’s Confession,” and “Hold Back Tomorrow.” So I was immediately keen to catch “Pickup,” his directorial debut in America (he previously enjoyed a sizable film career in the Czech Republic). Along with directing, Haas self-produced, co-wrote with Arnold Phillips, and starred in the picture as Jan Horak — a tender-hearted railroad dispatcher who attends a carnival looking for a dog but comes home married to the gold digging Betty (Beverly Michaels). Jan is too sweet of a man to see that Betty, who’s miserable living in the middle of nowhere at his depot, not only doesn’t love him, but is smitten by his young assistant Steve (Allan Nixon). When Jan suddenly goes deaf, Betty sees the disability as her chance to steal his money and bolt. Her plan goes awry, however, when Jan, after he miraculously regains his hearing, pretends to be deaf. “Pickup” features an impressive sound design, relying on high-pitch squeals to unmoor the viewer, and excels at a psychological seediness that is lean and mean yet filled with immense heart and warmth.

“The Glass Wall” (1953)

Playing at Locarno for the first time since it won the Golden Leopard in 1951, Maxwell Shane’s “The Glass Wall” is a vexing tale that puts America’s broken immigration system under the spotlight. Peter Kuban (Vittorio Gassman) is a Holocaust survivor who has stowed away on a ship heading to New York City. Once in America, he is detained, where he tells the story of how he helped save an American G.I. during the war. Unfortunately, he only knows the soldier’s first name — Tom (Jerry Paris) — and that he’s a clarinet player living in New York. None of those details are enough to guarantee his place in America; he needs to find the real Tom within 24 hours or he’ll be deported. Peter breaks out of custody toward Time Square to search for Tom, where, along the way, he meets helpful souls like Maggie Summers (Gloria Grahame) and a burlesque dancer named Nancy (Robin Raymond).

Gassman, an Italian actor playing Hungarian, is simply tremendous as Peter, demonstrating clear desperation yet a hopeful view of the world, despite his wretched circumstances, which gives this picture its moral compass. If a “model migrant,” in all the loaded connotations of the phrase, cannot hope to gain entry into America, then who can? That kind of question, which “The Glass Wall” raises, is one we’re still grappling with as many decry those who are not entering the country “the right way” without fully considering what a distasteful phrase — the years-long obstacles and boundaries thrown up at migrants — like that could possibly to mean those most distressed.

“Gun Fury” (1953)

As mentioned before, every film in the series, at least the ones I watched, screened at the GranRex Cinema. All of them except “Gun Fury,” a 3D western directed by the great Raoul Walsh. In the reconstructionist narrative, Rock Hudson plays Ben Warren, a pacifist with only two dreams on his mind: Marrying Jennifer Ballard (Donna Reed) and living far away from the troubles of the world on his massive ranch. Those dreams are shattered when Frank Slayton (Philip Carey), an outlaw haunted by the Lost Cause, robs a carriage carrying gold, shoots Ben and kidnaps Jennifer. When Ben awakens, he teams with Slayton’s former partner Jess (Leo Gordon) and with Johash (Pat Hogan) — an Indigenous man seeking revenge against Slayton — to hunt down the outlaw. Though the 3D in “Gun Fury” is mostly rudimentary, involving characters throwing objects at the lens, such as a loaf of bread, it’s still enrapturing to watch Walsh’s unparalleled sense of how to frame these vast landscapes and the way he captures the film’s immersive chases (at one point, we get a thrilling POV a shot from the driver of a wagon, as though we’re the ones holding the reins).

“The Last Frontier” (1955)

I am admittedly not a fan of Victor Mature. I just find his lackadaisical onscreen persona grating; I can never tell if he actually wants to be whatever movie he’s acting in. Nevertheless, I adore Anthony Mann — especially his long collaboration with James Stewart. And while Mature brings an unpredictable sense of intensity as the crude Jed Cooper — who along with fellow fur trappers Gus (James Whitmore) and Mungo (Pat Hogan) are enlisted by Captain Glenn Riordan (Guy Madison) to track an Indigenous chief named Red Cloud (Manuel Dondé) — I can’t help but feel he’s miscast here.

That doesn’t mean there aren’t fascinating elements to “The Last Frontier.” For a time it thrives as an anti-war and anti-military picture. Robert Preston appears as a General Custer-like figure, the bloodthirsty Colonel Frank Marston, whose wife Corinna (Anne Bancroft) is not only incredulous of her husband’s tactics but is also the apple of Jed’s eye. Preston provides the narrative with an easy villain to root against, one that embodies the rotten core of America’s Manifest Destiny. Jed’s desire to wear an blue army jacket is also nearly stamped out in a cathartic breakdown by Mature that demonstrates the emotional depths that always lurked underneath his stoic exterior but was rarely seen in his noir work. “The Last Frontier,” unfortunately, undoes much of that great, radical work by returning to normalcy and ultimately becoming the thing it so fervently seemed to hate — a blindly patriotic picture.

The Chinese WW2 spy thriller “Decoded” stands out for a number of reasons, mostly in spite of its conventional and hackneyed depiction of a troubled mathematician who deciphers encrypted messages for the mainland army. For starters, “Decoded” provides a dramatic change of pace for two marquee-worthy names: soft-spoken heart-throb Liu Haoran, who takes an unusual leading man role as the gifted, but painfully shy codebreaker Rong Jinzhen; and director Chen Sicheng, who’s best known for his goofy mega-blockbuster “Detective Chinatown” comedies. With “Decoded,” a plodding adaptation of Mai Jia’s popular source novel, Chen and Liu abandon cheap-seats humor—Liu co-starred in the “Detective Chinatown” movies, playing a straight man to comedian Wang Baoqiang—to pursue a more sober, but less convincing type of cornball power fantasy.

Liu also played a frustrated, but superhumanly gifted wallflower in “Detective Chinatown.” He was more convincing in those movies, partly because he was part of a winning buddy duo, but also because he wasn’t trying to capital-A act while wearing hairpieces, whose synthetic hairs thin at an alarming rate as his character ages. As Jinzhen, Liu brings to mind Russell Crowe’s performance as the schizophrenic mathematician John Nash in “A Beautiful Mind.” That association gets harder and harder to shake as Jinzhen inevitably loses his grip on reality while trying to solve the Black Cipher, a nigh-impossible encryption key that was specifically designed to stump Jinzhen.

Liu’s mostly compelling as a leading man whenever he can suggest a lot about Jinzhen by speaking softly and deferring his gaze, as if Jinzhen expects to be reprimanded or inconvenienced at any time. He’s still often eclipsed by co-star John Cusack, whose broad and twitchy performance often distracts from his dialogue, as well as a series of campy dream sequences that ostensibly speak for Liu’s introverted protagonist.

Jinzhen keeps a dream journal to help him break complex ciphers since the Freud-friendly symbols that he encounters in his dreams also help him to think out of the proverbial box. These dreams frequently hint at tensions that never gets resolved beyond portentous signs and awkwardly rendered computer graphics. Eventually, Jinzhen’s dreams overtake his waking life, which sinks “Decoded” deeper into a familiar and generally watchable scenario about a solitary genius’s triumph over impossible-seeming odds. But for a while, “Decoded” diligently and very slowly follows the various steps that lead Jinzhen along his defining quest to solve the Black Cipher.

Jinzhen passively tumbles from one encounter to the next throughout this 2.5-hour long dud. He’s first discovered by a distant relative, university professor Xiaolili (Daniel Wu), who adopts and nurtures Jinzhen. Then Jinzhen comes to the attention of Professor Liesiwicz (Cusack), a manic, but philosophically-inclined computational mathematics professor who refuses to collaborate with the Kuomingtang. “I hate war,” Liseiwicz declares at the end of an awkwardly phrased and negligibly dramatized speech. He’s soon forced to work for the American National Security Agency, for whom he devises increasingly difficult encryption methods, including the Black Cipher.

Jinzhen’s also reluctantly forced to crack codes for a world government, but he’s ok with it, since he occasionally recalls the unbelievable civics lessons that Xiaolili imparted to him in establishing scenes, in between one-sided chess games and stillborn dialogue exchanges with Liesiwicz. Jinzhen’s recruited by Director Zheng (Chen Daoming), a shadowy Chinese G-man whose pronounced limp and unyielding dialogue substitutes for an actual personality. Then Jinzhen’s sequestered in a secret government compound, where he develops a perfunctory romance with Xiaomei (Krystal Ren), whom he proposes to using hand-written cyphers and also sleeps with following a pseudo-suggestive exchange (“Layer by layer, the truth is unveiled”).

There’s no sex in “Decoded,” by the way. Instead, there are a lot of tacky, lavishly animated dream sequences, which often look like overproduced screensavers. Sometimes Jinzhen dreams about ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer), a wall-sized HAL-9000-type computer that taunts Jinzhen in fluent Mandarin by yelling cryptic things like, “You will never understand us.” Other times, Jinzhen dreams about the Beatles, since their song “I Am the Walrus” mysteriously holds the key to the Black Cipher. Unfortunately, it’s only so much fun to watch a sweaty, out-of-breath Jinzhen get chased around by four unconvincing Beatles stand-ins, who at one point sing, through imprecisely translated English subtitles: “I am the egg guy. We are the egg guys. I am the manatee.”

Liu doesn’t exactly light up the screen in his limited capacity as a humanoid plot device. His character either reacts to or follows after whatever promising new development might help Jinzhen to solve the latest problem that’s vexing him. The filmmakers do what they can to compensate for their unlikely hero’s prevailing lack of charm and agency, but not even the combined forces of Lloyd Dobler and the Fab Four can bring a spike of joy to this DOA period drama.

Immigrant stories put a fresh frame around lives that native-born citizens don’t think too deeply about. Science fiction movies can do the same, but in a more exaggerated fashion, revealing the surreal eeriness of the “normal.” You see this dynamic at work in “The Becomers,” writer-director Zach Clark’s movie about extraterrestrials coming to earth and assuming the bodies of humans. It’s probably more engrossing to just throw the movie on and let it unfold than to go into it after reading a review or summary. Any impact the movie has comes from the alternately comical and unnerving way Clark and the cast and crew choose to unveil each new bit of information, from the mechanics of body takeovers to the sex lives of these creatures (orifices are involved, though not the ones we’re used to).

Shot in greater Chicago, the movie throws you into the middle of its premise, and establishes right away that this is a science fiction movie that’s going to explore its ideas mainly from the points-of-view of aliens rather than the humans who encounter them. The main characters are two lovers from a dying world who’ve come here separately to reunite and make a fresh start and end up reuniting after some complications and living an outwardly typical suburban American lifestyle. The aliens are played by various actors, in the manner of a science fiction or horror film where creatures or spirits pass from one host to another. The main cast includes Isabel Alamin, Molly Plunk, Victoria Misu, and Mike Lopez, and the tale is occasionally narrated by Russell Mael in a not-quite-monotone that’s sneakily funny at times.

Everybody is on-point in terms of a unified mode of performance. The visitors are deadpan, quietly internal when dealing with humans yet super-alert, and a bit too cheerful-chirpy or overly invested in what they’ve learned about human life and how they’re chosen to represent or regurgitate our behavior. There’s a strangely touching shot of a “male” and “female” extraterrestrial couple lying on a couch together watching TV, and the woman stretches her long leg out and touches the man with her foot; it’s an unknowing parody of the way people who are physically intimate with each other express that with casual touch. Humans who interact with aliens in human skins know there’s something “off” but can’t figure out what it is. There’s also a shot of a character eating snack food out of a can with a spoon, and it might make you think about what it means to eat something out of a can with a spoon.

Disguises are necessary. The initial form of an inhabited human body has glowing fuchsia eyes. Special contacts are needed to cover this up. The anatomies of the creatures beneath human skins are glimpsed but not shown in totality. These visitors are giving very good performances as us, and anything that’s “not right” could be chalked up to them being humans who are a bit odd. Since everybody’s a bit odd once you get to know them, they can get away with a lot.

They’ve ended up in suburbia for whatever reason, and not the “American Beauty” or “The Graduate” kind of suburbia where yuppies in expensive clothes drive fancy cars while thinking about the empty materialism of their lives. This is a more, er, earthbound kind of suburbia. Car culture rules supreme. People shop at convenience stores and discount clothing stores. Something about the way Clark and cinematographer Darryl Pittman shoot their real-life locations, including a standard-issue “motor lodge” motel and a cookie-cutter suburban house, evokes a secondary point of interest in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho”: the way the film captures what the United States looked like in the middle of the 20th century, when the interstate highway system was being built, a lot of smaller towns were being bypassed and forgotten and choked off from prosperity, and the “freedom” of the open road transmogrified into fearfulness and despair if you were running away from something instead of towards something.

I’m not sure that Clark has enough gas in the tank to carry the movie’s premise through the entire running time of a feature (though this is a short one by Hollywood standards). And the movie becomes less special and simultaneously more heavy-handed and diffused when our main couple falls in with a cult whose behavior makes them seem like a parody of extreme MAGA or QAnon, and the movie gets bogged down in a black-comedy political kidnapping plot. But “The Becomers” is still an arresting movie, and a great example of how to do a lot with a little.

The center of interest in terms of drama and comedy is really the central relationship between the extraterrestrial couple. It’s simultaneously a parody of American middle-class notions of contentment yet at the same time a disarmingly sweet and sincere endorsement of it. At points during the movie’s middle section, I was reminded of David Cronenberg’s “The Fly,” which used science fiction and body horror to explore the full arc of a committed relationship, including the “in sickness and in health” part of marriage vows. As Mickey & Sylvia sang in their classic song, love is strange, but also the most comforting thing in a disordered world.

One of the shining jewels of Apple TV+’s lavish yet underseen output—”Ted Lasso” and “Severance” aside—”Pachinko” stood out in 2022 as one of the most layered, complex shows on the streamer. An epic, novelistic tapestry woven through generations of a Korean family’s struggle through Japanese occupation, cultural assimilation, and all manner of personal boondoggles. While the first season adapted approximately half of Min Jin Lee’s sprawling book, the second season opens up the emotional floodgates even further, while focusing its structure and forging intriguing new dynamics for its characters caught between cultures.

The twin poles around which “Pachinko”‘s narrative revolves are Sunja (Minha Kim as a young woman in the 1940s and ’50s; Oscar winner Yuh-jung Youn as an old woman in 1989) and her American-educated grandson Solomon (Jin Ha), showrunner Soo Hugh’s complex narrative paralleling their anxieties and ambitions across decades. While the first season also focused on Sunja as a child, season 2 leaps forward to 1945, as she ekes out a life in Osaka selling kimchi with bartered materials and trying to care for her young sons, the studious but tortured Noa (Kang Hoon Jim) and the adorable, expressive Mozasu (Eunseong Kwon). But rumors spread of an impending American bombing, and Koh Hansu (Lee Min-ho), a man with a history with Sanju and sketchy business interests to protect, struggles to balance those designs with the desire to protect Sanju and her family. In the 1980s, she’s mostly a source of quiet support for an older Mozasu (Soji Arai) and Solomon but yearns to find comfort in the presence of a new friend she’s gradually courting (Jun Kunimura).

Meanwhile, in 1989, Solomon still reels from the decisions he made at the last season, in which he passed a test of moral certitude, but it resulted in professional disgrace. Now, he tries to recover from the stumble in his career and build himself back up, but the compromises come gradually and overwhelmingly as he’s drawn back into old relationships and the ever-present tug of war between his Korean and Japanese identities.

His struggle this season is similar enough to season one that his stretches become a bit less interesting—will he learn to prioritize family over business—but they track quite elegantly with Sunja’s struggle for a better life in Japan-dominated Korea. Through these parallels, you see the lineage of struggle, and the back and forth between the obligation we feel towards those who came before and our need to forge our own paths.

Hugh draws these lines so considerately, the timelines becoming more intricately woven together as the season progresses and they grow closer in chronology. The comforts of the present contrast with the agonies of the past, linked through smart editing and Nico Muhly’s plaintive, heartstring-tugging score. The performances remain uniformly excellent, especially Ha and Youn as Sunja at two distinct, but no less profound, eras in her life. (It’s not all bombed-out cities and star-crossed love, however; the show’s exuberant title sequence, always a show highlight, gets an upgrade here, with the cast dancing in Mozasu’s pachinko parlor to The Grass Roots’ “Wait a Million Years.”)

As one character notes late in the season, trying to win at pachinko is a fool’s errand—it’s folly to think that applying the right amount of pressure or timing your flicks will make you win the game. As with life, pachinko is a game of chance; any sense of control is an illusion. That’s a perfect parallel for the show’s tragic sweep, a cast of characters tossed to and fro by the winds of war, heartbreak, ambition, and loss. “Pachinko” is the kind of show that, like a good batch of kimchi, gets better and more flavorful as it ferments. I can only imagine future seasons will expand the show’s palate and bring out an even richer experience.

Entire season screened for review. Pachinko airs Fridays on Apple TV+.

Not gonna lie, this had me in the first half. In its first hour, Tina Mabry’s “The Supremes at Earl’s All-You-Can-Eat” is a bubbly, melodramatic story about the multi-decade friendship shared by three Black women. Based on Edward Kelsey Moore’s same-titled novel, the comedy zigs—despite its name, it’s not actually about the musical group—and zags through these characters’ personal ups and downs. In some ways, its tonal shifts, light and airy, mirrors the tone seen in Black 1990s films like “Soul Food” and “The Best Man,” where the overriding love shared by the characters help them overcome seemingly insurmountable personal challenges. And, for a time, Mabry’s film is a wonderful addition to that canon.

The non-linear story begins with a tired Odette Henry (Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor) sitting underneath a tree. She recounts how her pregnant mother, worried about baby Odette’s arrival, sought help from a witch, who recommended that she sit atop a sycamore tree. There, Odette was born. Ever since then, she has been fearless. Through her eyes, we leap to 1968: Odette (Kyanna Simone plays her in her younger years) has dreams of becoming a nurse while her best friend Clarice (Abigail Achiri), a talented pianist, seems destined for a recording career. The pair befriend and save Barbara Jean (Tati Gabrielle) from her abusive stepfather following the death of her alcoholic mother, finding her a home with Earl (Tony Winters) and his wife at their family-owned diner.

These early scenes are among the film’s strongest, fashioning a believable bond between these seemingly disparate people that makes the nickname many attach to them, “The Supremes,” apt. However, as we transition into their adulthoods and later years, the film unravels so quickly that it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly where this initially enjoyable film flew off the rails.

The early scenes, set in the late 1960s, certainly have flair. The period costumes are colorful and varied, leaning toward bright yellows and oranges. There is also some steaminess. Barbara Jean, for instance, falls for Chick Carlson (Ryan Paynter)—a white busboy working for Earl, who is also a survivor of physical abuse. Within the racist milieu, Chick’s brother is a crazed, violent bigot; Chick and Barbara Jean’s love creates an intriguing bit of tension that the film, confusingly, lets fall away.

Rather than tell a simple story of uncommon friendship, the film overreaches. When we flash forward to the present day, all of the women are working through deep hurts. Earl, their father figure, has passed away, leaving his superstitious widow (Donna Biscoe) and his level-headed son in charge. Barbara Jean (Sanaa Lathan) is on an alcoholic spiral after watching her present husband, Lester (Vondie Curtis-Hall), suddenly pass away. Clarice (Uzo Aduba) gave up on her dream of being a pianist, and now it seems like her husband Richmond (Russell Hornsby) might be cheating on her. Odette has a delightful, healthy marriage with James (Mekhi Phifer). But her life is upended with a sudden diagnosis of non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Somehow, that only scratches the surface of all the plot’s varied surprises.

In the film’s final half hour, the script seemingly throws another movie’s worth of sharp turns and unlikely leaps: divorces, murders, and tragic deaths that are juxtaposed by a taste for melodrama and an appetite for mordant humor. In fact, I’m still not entirely sure what I watched. I’m not sure any of the cast knows either. Despite their best efforts, their commitment goes for naught as their characters—in a film that clearly wants to be a kind of soap opera—make the most absurd decisions. Ellis-Taylor, who is riding an exceptional hot streak, mostly holds it together, but even her incredible talents can’t keep some scenes from devolving. Lathan is equally helpless as her character’s most outlandish beats startlingly become afterthoughts.

Between the eye-catching period details and the warmth of the performances, you want to wrap your arms around “The Supremes at Earl’s All-You-Can-Eat.” But this is a film that seems intent on pushing you away through its ludicrous plotting. There is a touching story here about Black women with high hopes running into life’s crushing realities lurking somewhere in the middle of this tangled, knotty work that essentially suffocates itself. But Mabry’s good intentions aren’t enough to save what feels like an insignificant work compared to its high ideals.

The Adams Family—a group of filmmakers led by father John Adams, mother Toby Poser, and daughter Lulu Adams—are some of the most fascinating horror filmmakers on the scene. Get thee to a streaming service and watch “The Deeper You Dig” as soon as possible—it’s one of the best horror films of the decade so far—and then chase that with their clever, twisted “Hellbender.” These are deeply personal genre films, movies that hum with atmosphere and dread. Their latest is kind of a departure for John and Toby—Lulu gets writing credit but doesn’t appear this time—in that it’s their first filmed on location out of the country (in Serbia) and easily contains their biggest budget. Working with a bigger production company on a film that feels more like anyone could have made it then their previous works drains “Hell Hole” of some of the DIY charm of the other flicks by Adams and Poser. Comparatively, it’s kind of a disappointment, despite having some undeniable positives that should make it an easy watch for horror heads.

“Hell Hole” was obviously inspired by the master John Carpenter, owing a great deal to his version of “The Thing”—a remote outpost overtaken by a monster that can look like an ordinary person—and movies he made about people essentially stumbling into portals to Hell in films like “Prince of Darkness” and “In the Mouth of Madness.” The hapless souls in this one are a team (led by Poser’s Emily) that’s fracking in a remote corner of Serbia when they drill into, well, something impossible. They find a body in a sort of cocoon of a centuries-old soldier, and he’s still alive. While they discuss what to do with this break in reality, they notice something even stranger about the Frenchman in that there appears to be something that occasionally peeks out of his nose or ear. Before you can say “burn it with fire,” the monster that was inhabiting the poor soul has jumped ship to John (Adams) and set out to wreak more havoc.

The main twist of the body possession tale here is a sort of male pregnancy narrative in that the creature is inhabiting men as a host for growth. Where’s mom? And what happens when it comes to term? The Adams Family has a lot of fun with some of their most out-there ideas, such as when the creature in a human host realizes it’s under threat and basically just flees by turning its current home into a pile of bloody goo. “Hell Hole” is a marvelously goopy movie with a whole lot of slimy red stuff and tentacles slicing through the air. It’s also a consistently funny movie, playing almost more like dark comedy than the foreboding work the family has made in the past.

On that note, I’m happy to see Adams and Poser kind of spreading their wings and trying something different here, but it’s hard to shake the feeling that this one doesn’t have the same teeth as their best work. It’s more of a lark. Sure, there’s some commentary about how f-ing with Mother Nature will eventually lead to carnage, but it’s very loosely sketched, and the characters have too few traits to be actually memorable. Yes, it’s a bit clever that Emily used to be a hippie, and there’s some decent character work by Olivera Perunicic, but the people here are naturally forced to cede interest to the enemy they face, giving the whole thing a sense a bit of a shallowness that even great body horror avoids. It’s sporadically fun enough, but not that deep a cinematic hole.

Nathan Silver’s “Between the Temples” opens with a loud, keening blast from the shofar. If you haven’t heard it before, imagine the sound of someone slumped forward in the driver’s seat, face pressed against the steering wheel, and you’ll be in the ballpark. It’s a perfectly bracing note to open this year’s most anxious comedy, about a cantor in a crisis of faith who has recently lost his wife, his voice, and his will to live.

Antic, endearing, and often achingly funny, the film stars Jason Schwartzman as Ben Gottlieb, who hasn’t felt at home in his sleepy upstate New York community since the death of his novelist wife in an accident months earlier—literally, given that he’s moved back in with his overbearing mothers (Caroline Aaron and Dolly De Leon), whose well-meaning if clueless efforts to get him back in the dating game haven’t exactly lifted his spirits. (“In Judaism, we don’t have heaven or hell,” Ben cracks with a small smile. “We just have upstate New York.”)

Unable to get the words out when asked to sing at his first Shabbat back at the pulpit, Ben flees the synagogue still wearing his tallit and walks home in the dark, replaying his wife’s dirty voice messages until he abruptly has had enough and lies down in the road. An 18-wheeler rounds the bend but stops just short. “Keep going,” he begs. “Keep going, please!” Humiliating and profound, this punchline isn’t quite introductory—indeed, it’s hard to think of another comedy that starts so strikingly in the moment as this one—but it evokes the dynamic, dizzying swirl of pain and pleasure that, as devised by Silver and co-writer C. Mason Wells, constitutes the film’s comic locus.

Naturally, the driver can’t grant Ben’s request, but he does drop him off at a dive bar, where he throws back mudslides, gets punched out, and at this lowest of lows encounters his grade-school music teacher, Carla Kessler (Carol Kane), herself a widow in search of her next chapter. Though his mothers make no secret of their eagerness to set him up with a nice Jewish girl—perhaps Gabby (Madeleine Weinstein), the daughter of their local rabbi (Robert Smigel)—Ben finds himself spending more time with Carla instead. In hopes of reconnecting with their Jewish roots, Carla has decided she wants to finally have the bat mitzvah denied to her all those years ago by her Russian Communist parents and that she left behind when she married her now-deceased Protestant husband—and she wants Ben to give it to her. He’s caught off guard when Carla suddenly appears at the synagogue and signs herself up for lessons, given how much older she is than his typical students, but she only has to twist his arm so far before Ben gives in.

After all, they’re kindred spirits, in ways immediately obvious and less so; both have lost their spouses, but Ben and Carla are drawn to each other for more reasons than their mourning. Ben remembers “Mrs. O’Connor” as a warm and encouraging teacher, though the cantor’s even more taken with her candor—she doesn’t remember him at all, she says—and garrulous demeanor, not to mention the freedom he senses in her selectiveness with following only the religious customs that suit her. Carla, meanwhile, admires Ben’s sensitivity to faith and that he listens when she speaks to him. Both have been kicked around by life and sense in each other a tendency to keep laughing through the pain—even if, before this point, only miserably and to themselves. Perhaps the unexpected ease of their friendship makes it so undeniable. Bonding over Hebrew lessons, non-kosher burgers, and mushroom tea, these two improbably help each other out.

This is Silver’s ninth feature and, like his previous ones, it revels in capturing the alchemical, off-kilter chaos of oddballs in proximity; what makes it special has as much to do with the strange, spontaneous energies that fill the air between his characters as what it is they’re saying. “Between the Temples” could be broadly described as a behavioral comedy; it’s not a critique of organized religion but an empathetic study of how people constantly organize and reorganize their relationships to religion—and within that, their relationships to themselves and one another, in response to constantly fluctuating cross-currents of need, desire, and circumstance.

To that end, Schwartzman and Kane make for a winning screen duo, their chemistry alternately jagged and tender as Ben and Carla settle into a kind of shared neurosis—not a discovery nor a delusion, but something in between—that neither can quite define or really cares to. Schwartzman, so affecting in last year’s “Asteroid City” as another widower stopped by sorrow, plays Ben as a more slack, disorderly sad-sack whose grief has blotted out his sense of self. That’s until Kane, with her zany comic stylings and that unmistakable voice, enters the frame with the irrepressible zest of a rising sun, clearing his clouds away; with her curiosity, ebullience, and raucous humor, Kane is the film’s animating force.

Both actors are elevated by a note-perfect ensemble, including a particularly welcome Smigel (known best for his work in a very different comic register as the puppeteer and voice behind Triumph the Insult Comic Dog) as a rabbi who, focused less on faith than finances, putts golf balls into the shofar, as well as relative newcomer Madeline Weinstein as his newly single daughter, Gabby. Though she enters the film an hour in, Weinstein shakes up its second half while enabling two of its standout sequences.

An anxious actress who’s returned home after a failed engagement, Gabby struggles as much as Ben to get her head on straight, as becomes apparent during an erotically charged interlude in a Jewish cemetery that’s about as morbidly hilarious as “Between the Temples” gets. In terms of soul-deep discomfort, though, it has nothing on a disastrous Shabbat dinner at which an intricate latticework of emotional dynamics—confessions, grievances, revelations, humiliations—comes undone in such transcendently shambolic fashion that one suddenly sympathizes with how the door to Ben’s basement door keeps shrieking with the agony of thousand damned souls.

“Between the Temples” was shot in gloriously textured 16mm by frequent collaborator Sean Price Williams, at this point a mainstay of the New York independent film scene whose expressionistic lens is second to none when it comes to capturing the beating heart of chaos. The sense of total immersion in a scene his handheld camera conveys (especially his electrifying focus on faces and facial reactions) modernizes the film’s screwball melodrama. He observes the minutiae of human interaction, often in tight close-ups that move in concert with rapid-fire volleys of incisive dialogue to reach past characters’ deadpan self-defense mechanisms and reveal poignant inner tensions. John Magary’s unpredictable editing, with its skewed staccato rhythms, provides the film with a cheerfully chaotic locomotion that does perhaps even more to keep the audience on their toes.

The film’s premise most immediately recalls the bittersweet May-December romance of “Harold and Maude,” a comparison that the presence of Schwartzman—a frequent collaborator of Wes Anderson, whose tragicomic sensibility and affinity for eccentrics, underdogs, and Cat Stevens certainly owe a debt to Hal Ashby—makes unavoidable. But Silver is working in a more warmly improvisational key, letting in both light and life with such buoyant naturalism that you don’t question the honesty of his characters’ questioning nor the humility—and humanity—of their struggle to self-determine. There’s a core sweetness to “Between the Temples” that shines through. Gently but firmly, the film insists upon the miraculous nature of all the meandering paths we end up taking: in search of our lives, without a clue where we’re going, toward those who’ll give us meaning.

“Between the Temples” is in theaters Friday, via Sony Pictures Classics.

Early in Zoë Kravitz’s directorial debut, we are introduced to Slater King (Channing Tatum), a tech billionaire, via a television interview where he apologizes for an undisclosed offense. However, the unsaid transgression is no mystery. The setting—an influential, rich white guy in a confessional interview lamenting his behavior and promising to do better—is a familiar enough scenario that we can assume he weaponized his power in some egregious manner.

Slater hosts a gala where catering waitresses and best friends, Frida (Naomi Ackie) and Jess (Alia Shawkat), are working. Halfway through, they ditch their white button downs for cocktail dresses in the hopes of schmoozing with the man of the hour. When Frida’s accidental faceplant draws his attention, the girls get exactly what they were hoping for. Spellbound by his handsome looks, status, and confidence, when he invites them to his island for a vacation full of lavish poolside partying, they jump at the chance.

Joined by his cabal of miscreants—Cody (Simon Rex), Vic (Christian Slater), and Tom (Haley Joel Osment), and their invitees, Sarah (Adria Arjona), Heather (Trew Mullen), and Camilla (Liz Caribel)—Slater boards a private jet for the supposed getaway of their dreams. With their cell phones collected by Slater’s nervous and neurotic personal assistant and sister (Geena Davis), everyone is left to revel in the indulgences the island has to offer, be it weed, bottomless champagne, or elaborate nighttime dinners. Yet as the boozy days blend together, a sneaking suspicion begins to arise that something isn’t right.

“Blink Twice” believes it has a point to make about the sinister capabilities of rich white men, but it does nothing more than call it out. The writing stops at square one. It doesn’t engage with its proposed thesis, but instead makes a chop shop of buzzwords and hot topics from #MeToo to therapy bros. When the reveal of “Blink Twice” enters via a split-second frame, the shock of the film turning on its head is not one of horrifying suspense, but rather, dejection. And as the quick frame devolves into extended sequences of brutality into a cutthroat race to the finish, the film becomes an affirmation of a tired, simple narrative toolbox being sold as unflinching feminist grit.

“Blink Twice” sucker punches the audience with its sexual violence and then fails to find intelligence or dexterity in its handling of it or any of the themes running adjacent. Even the stylistic choices, with which the film rides on, are simple. And as the film tries to balance its tone and events with humor, it only belies the success of itself further. It’s unfunny. “Blink Twice” doesn’t earn a laugh when it’s trying to be fun, nor does it elicit a chuckle when collating an act of brutality with a punchline.

Of all the film’s infractions, the impact of its sloppy logic isn’t primary, but worth noting. The laws by which Slater is able to weaponize his power are inconsistent and confounding once you dip a toe past the surface. If there’s anything to be credited here, it’s the performances from the cast. From his heartthrob origins to “21 Jump Street,” where Tatum debuted his comedic chops, “Blink Twice” shows he’s formidable at tackling darkness too, and that he can indeed be a feared presence onscreen. Ackie manages well in her starring role, with the expressiveness of her eyes locking us in, and her chemistry with Arjona’s Sarah giving us a crutch with which to limp to the film’s conclusion. Yet even with their best efforts across the board, “Blink Twice” has already failed on paper. It is homespun exploitation followed by a pretentious conclusion that smirks at the viewer, declaring prideful resolution.

Kravitz’s leap toward discomfortable should not be misinterpreted as an auteur’s valiance. If we as viewers equate the brazen with the brave, our expectations are far too low. Courageous storytelling requires thoughtful engagement and nuance. Kravitz displays neither, opting for textbook exploitation while feigning sharp wit. She wields her blade haplessly, drawing blood from the women that “Blink Twice” is supposed to (eventually) empower.