If you want to know how difficult it is getting 70mm film prints screened at movie houses these days, just talk to Jerry Blackburn. Blackburn is the senior manager and director of public programming for the Beverly Hills-based Fine Arts Theatre. Built in 1937, the repertory theater is one of the handful of historic movie […]

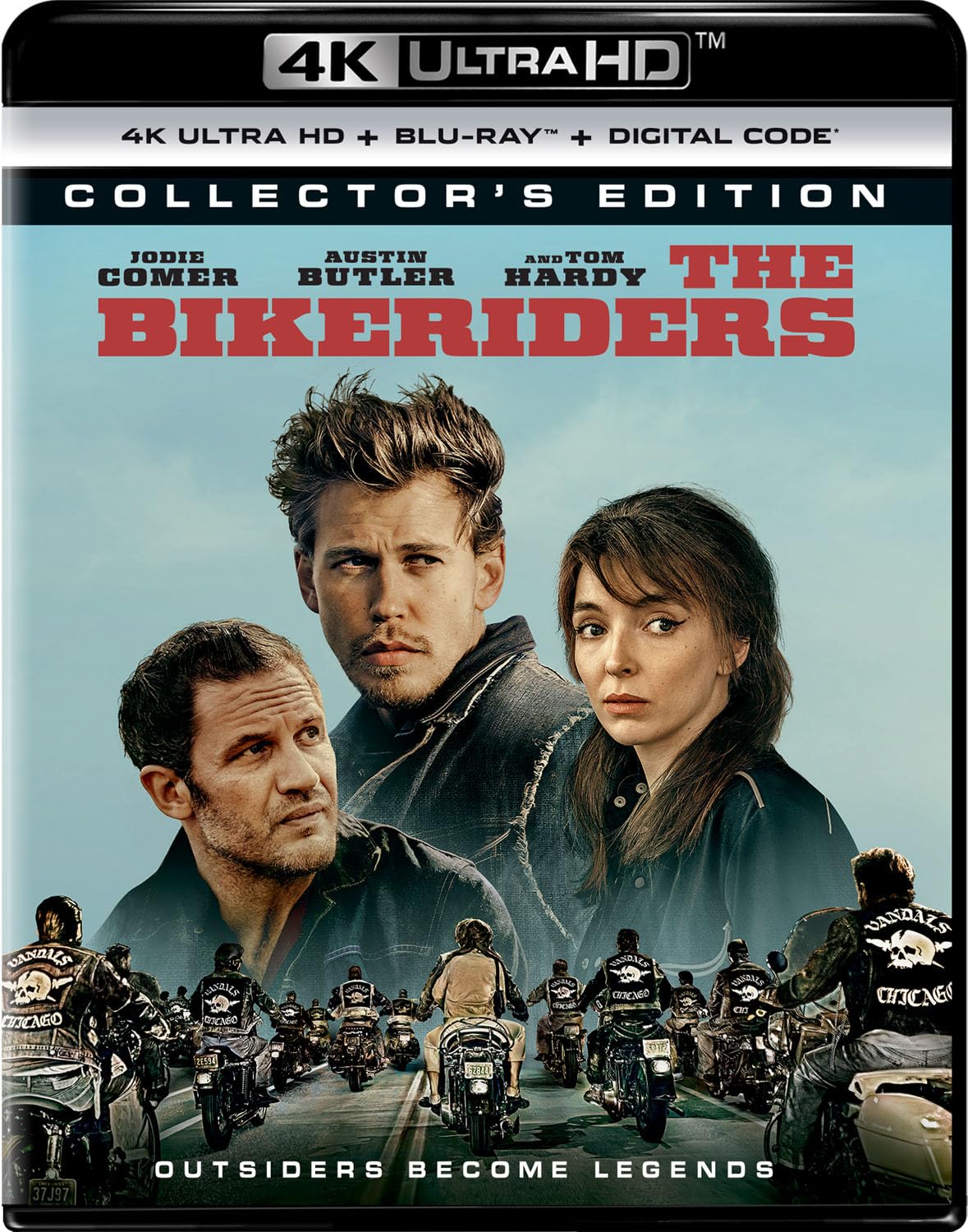

The latest on Blu-ray and streaming, including The Bikeriders, Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga, IF, and The Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes.

A review of the latest Netflix animated series, based on the timeless James Cameron films.

The Rings of Power expands and improves in a confident second season.

We usually devote our video game coverage at RogerEbert.com to titles with a connection to cinema, whether it’s a series that inspired movies like “Resident Evil” or titles that drew upon a history of movie adventures to tell their tales like “Uncharted” or “The Last of Us.” However, every once in a while, there’s an […]

The Biennale de Venezia, cinema division—we should not forget that this festival encompasses other forms over the course of a year, including fine art—kicks off this week. It’s a storied, venerated festival in a storied, venerated setting, and it’s a real privilege that I’ve been able to attend every year (except 2020, because of COVID, […]

Locarno isn’t a film festival. It’s a pilgrimage. My journey to the legendary festival, which celebrated its 77th edition this year, involved planes, trains, and automobiles to land in Milan, Italy before crossing the border into Locarno. The odyssey felt well worth it when I caught sight of the narrow stone pebble streets, the gelato-colored […]

The Criterion Collection may have surprised some collectors when they announced last May that they would be releasing two Albert Brooks movies on their label in August: “Real Life” and “Mother.” “Real Life” was not a surprise. An HD treatment was long overdue and had been a favorite for so many Brooks fans and fans […]

The ambition of Ubisoft’s “Star Wars Outlaws” constantly battles with the execution in a game that’s alternating invigorating and frustrating, a title that feels like it has boundless potential that also feels like it traps you in the same repetitive mechanics. It also suffers from a too-common problem of AAA games in that it’s unacceptably […]

FX has more than earned the benefit of the doubt when it comes to comedy. Not only have they displayed a willingness to embrace creative voices with all-timers like “Better Things” and “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia,” but they’re arguably the most critically acclaimed home for the genre of the current decade with the trifecta […]