Compared to Jan de Bont’s beloved original, this long-gap sequel barely kicks up dust.

The post ‘Twisters’ Review: Lee Isaac Chung’s Nostalgia-Chasing Sequel Is a Category Five Letdown appeared first on Slant Magazine.

Compared to Jan de Bont’s beloved original, this long-gap sequel barely kicks up dust.

The post ‘Twisters’ Review: Lee Isaac Chung’s Nostalgia-Chasing Sequel Is a Category Five Letdown appeared first on Slant Magazine.

Is it love at first sight? Can enemies ever become lovers? The new comedy-adventure romance series is now streaming on Crunchyroll.

While it may be a while before we see his portrayal of Donald Trump in The Apprentice stateside, Sebastian Stan delivers one of the best performances of the year in A Different Man. Written and directed by Aaron Schimberg (Chained […]

The post A DIFFERENT MAN Trailer: Sebastian Stan Changes His Face & Life in Aaron Schimberg’s Surreal Comedy appeared first on Hammer to Nail.

Michael Mann’s research into and hands-on approach to his work would make even the most committed artist blush. God knows how deep the cabinets and shelves on each project––especially the ones that never got made––truly run, and it’s the nature of Mann fans to never feel like there’s quite enough: years between films while every […]

The post Michael Mann Launches New Online Archive and Provides Heat 2 Update first appeared on The Film Stage.

Following the release of his groundbreaking dark comedy “Dr. Strangelove” in 1964, the subsequent films made by the late Stanley Kubrick would all undergo similar fates regarding their initial and ultimate critical receptions. Upon their initial releases, they would receive polarizing reviews critiquing everything from Kubrick’s formal approach to how failing to live up to critics’ expectations. With time, however, films that had initially received varying degrees of scorn and confusion would be celebrated as masterpieces, often by the very same people who dismissed them the first time around.

For example, take “The Shining“: When it first came out, there were complaints across the board about its deviations from the text, the over-the-top performances from Jack Nicholson and Shelley Duvall, and its slow pace. Nowadays, of course, it’s regularly considered one of the greatest horror movies ever made.

Therefore, it shouldn’t be surprising that Kubrick’s final film, “Eyes Wide Shut,” would receive a similarly chilly reception when it first hit theaters in July of 1999. Thanks to the combination of natural interest in Kubrick’s first film since 1987’s “Full Metal Jacket,” his sudden passing a few months earlier, the presence of Hollywood’s hottest couple at the time—the then-married Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman—and an ad campaign that suggested a boundary-pushing erotic thriller beyond the likes of anything Hollywood had ever seen before, interest in the project could not have been higher. While it did get some good reviews here and there, it was largely dismissed by critics who found it pretentious, lugubriously paced, and, most of all, not sexy. As for audiences, they flocked to it during its opening weekend, only to discover that the film that they had been primed to see, one in which they would theoretically get to see two of filmdom’s most glamorous stars getting it on, was not the one that Kubrick gave them. They responded accordingly—the box-office receipts plummeted after a big opening weekend and the film received a “D-“ CinemaScore rating.

It’s now 25 years since the film’s debut and, perhaps inevitably, it has gone through its own period of critical reevaluation. What they’ve discovered (and what some of us have known from the start) is that “Eyes Wide Shut” is a film like no other—a strange, unsettling, and provocative exploration of marriage and sexual jealousy as defiant of expectations as anything that Kubrick ever made. It can also be seen as the culmination of an era in screen history: just before American cinema became almost entirely dominated by sequels, remakes, reimaginings and adaptations of comic books, here was a film that took its blockbuster-worthy elements and put them in service of an adult-oriented movie.

Like every film Kubrick made since “The Killing” (1956), “Eyes Wide Shut” was inspired by a previously published work, in this case, Austrian author Arthur Schnitzler’s 1926 novella “Traumnovelle,” also known as “Dream Story.” Kubrick first encountered the works of Schnitzler, who was celebrated for his controversial, psychologically-driven explorations of sexuality, and was particularly taken with “Traumnovelle” and its meditation on erotic ambiguities occurring within the context of a seemingly happy, stable, and comfortable marriage. He acquired the film rights to it in the late 1960s but was stymied by how to best approach it in cinematic terms, though he would always return to it while in between projects.

After years of trying to do it as a low-budget comedic exercise in sexual frustration—at various points contemplating such potential stars as Steve Martin, Albert Brooks, Woody Allen, and Bill Murray—it was finally revived in 1994 when he and screenwriter Frederic Raphael, whose script for the 1967 cult favorite “Two for the Road” also depicted a married couple dealing with strains in their relationship, reworked and expanded the story. They relocated the story and characters to contemporary New York and took a more serious approach. Urged by Warner Brothers to cast stars in the leads, he contemplated hiring Alec Baldwin and Kim Basinger in the main roles, but after meeting with Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, he awarded them the parts.

People thought that it was too slowly paced, that Kubrick’s recreations of New York City on a London soundstage were weirdly unconvincing, that the plot made precious little sense, that the sexual attitudes on display seemed wholly unrelated to contemporary concerns, and that Cruise and Kidman displayed little of the star chemistry that they were presumably hired to provide. Mostly, they wanted to see the gripping erotic thriller promised by the trailer and the incessant rumors that had sprung up over its extended production period. Kubrick could have easily given them a film more or less along those lines, which could have resulted in something brilliant. However, he was clearly after something much different than that. This constantly challenging work not only saw him defying the expectations of those hoping to see a sexy drama featuring two big stars as well as those of people who thought they were familiar enough with Kubrick and his work to see what he might do, only to be similarly hampered by the results.

This was a project that long consumed and intrigued him, even as other long-gestating projects like “Napoleon” and “A.I.” fell by the wayside after years of planning, and you can feel that in virtually every frame. Although pretty much all of Kubrick’s films, save for “Spartacus,” were “personal” in the sense that he more or less controlled them, his connection for the material here clearly went far deeper, in ways both obvious and discreet. The sense of ironic distance he frequently employed in his work is almost entirely absent here. As someone who was himself married three times during his life, Kubrick no doubt found himself mulling over the questions raised by the material regarding marriage, love, fidelity, and jealousy and saw Schnitzler’s narrative as an excellent method to wrestle with those notions.

His other films may have contained grand universal ideas that viewers worldwide could connect to. Still, the ones on display here are presented in an almost disconcertingly direct manner that may have rattled viewers like Alice’s revelations rattle Bill. (There are also numerous personal touches strewn throughout the film: Bill and Alice’s apartment was apparently based upon the New York apartment where Kubrick and his family lived before making a permanent move to England. There’s also the use of a clip from “Blume in Love,” a 1973 about sexual jealousy made by Paul Mazursky, an old friend of Kubrick’s who co-starred in his first film, “Fear and Desire.”)

As for the particular complaints regarding the film at the time, each has an answer, though some may require at least a second viewing to pick up on them. Yes, by all logical standards, “Eyes Wide Shut” doesn’t make a lot of sense, because Bill’s extended journey into the night and subsequent attempt to replicate his moves that make up its long central section do not adhere to any real logic. This goes especially for the incredible amount of activity that Bill can pack into what is already a late night. The answer, of course, is that pretty much all of it is meant to be a dream, which shouldn’t come as a surprise considering that the usual translation for the source book title is “Dream Novel.” Of course, claiming that something is all a dream is about the laziest narrative gambit, but in this particular case, it makes a lot of sense. It allows even the most seemingly mystifying elements of the film to fall into place.

But where does the dream/nightmare actually begin? The opening scenes, for example, are quite real in the way that they establish Bill as someone who constantly lives in the shadow of people with the kind of power and prestige that he quietly craves. Yes, he is a successful doctor, but only to a certain point—his initially impressive apartment pales in comparison to the lavishness of Ziegler’s residence (compare Bill and Alice’s cramped bathroom with the spacious lavatory where Bill brings Mandy back to consciousness). When we see Bill at work at his practice, we find that he shares it with another doctor. His discussion with Alice about fidelity, jealousy, and gender expectations may be fueled by almost ridiculously strong pot (somewhere out there, a resourceful pot grower/cinephile needs to create a strain called “Alice’s Recrimination”). Still, the feelings and resentments espoused by the two are achingly, bruisingly real. Kidman is, of course, an exemplary actress. Still, her work in this scene is arguably the single best bit of work that she has done to date—even though her screen time trails off considerably at this point, her presence looms over everything to come.

It’s at this point that Bill slides into a pot-induced dreamland kicked off when he’s summoned to his dying patient’s bedside. The unlikeliness of the time frame is no longer an issue, since dreams do not have to correspond to reality in this regard. At the same time, a number of the affectations Bill employs throughout—his habit of handing out a seemingly endless amount of cash during his nocturnal adventures without ever apparently hitting an ATM or the way he displays his medical identification card as a way to get in to anyplace he please—makes a lot more sense. These are the symbols of his position and authority, and in a dream state, they never run out or find themselves challenged. This also explains why the vision of New York we see during Bill’s journey never quite feels realistic. It’s as if it is a version created in somebody’s mind, and everything from newspaper headlines to store signs seems to be all but commenting on the unfolding action.

At the same time, Alice’s revelations about her sexual desires have shaken Bill’s confidence in both her and himself to such a degree that they wind up dominating and subliminally emasculating him at every turn. No matter how young and with it he may seem, as he reveals in his argument with Alice, he is not the most progressive of people when it comes to matters of sexuality—even when he finally gets a look at the orgy in action, it proves to be a curiously unerotic spectacle that looks more like a bizarre museum exhibit on The History of Kink.

The idea of his wife being someone with sexual thoughts of her own that don’t include him is such a distraction that they essentially undercut his reverie by throwing bizarre roadblocks at him every time he comes into contact with another woman who demonstrates even the slightest hint of desire towards him. In this regard, the decision to place CGI figures to block some of the more explicit imagery in the sequence to earn the commercially necessary “R” rating could have proven to be a clever bit of business—even in his mind, he is prevented from seeing “the good parts”—if it hadn’t been undone by clumsy execution.

(If Kubrick had not passed away during post-production, he would likely have fought tooth and nail to get the film released with an NC-17, which might have ended the long-standing commercial stigma towards that rating, or, barring that, would have made such additions/edits to the scene in a more artful manner than was done.)

Watching these scenes, it is easy to see why Kubrick first thought of doing this with actors more associated with comedy. The scenes in which Bill is thwarted work as a sly comedy of sexual frustration. But what makes them work so well, both as dark comedy and discomfiting drama, comes from Cruise’s genuinely inspired casting. Both before and after “Eyes Wide Shut,” Cruise has played glib heroic types who always get the job done, and while he has primarily eschewed films with heavy erotic content (save for this and the classic “Risky Business”), he almost always gets the girl in the end. So watching him constantly fail, combined with Cruise’s obvious discomfort at playing someone incapable of rising to the occasion, so to speak, adds a disconcerting edge to the proceedings. It’s pretty brilliant, leaving viewers with the same frustration as Bill at being the star of his extended sex fantasy and still not getting any when all is said and done.

Of course, all dreams must come to an end, and Bill, now confused and at wit’s end, demands an explanation for everything he has experienced to make sense of it all. It comes in the form of Ziegler, the man he yearns to be like one day and whom he has gone above and beyond for in the past in the hopes of one day rising to his level. Ziegler proceeds to lay out an explanation that covers everything that Bill has experienced while admonishing him on the potential dangers if he tries to probe what happened any further. It all sounds so convincing in the retelling—aided in no small part by Pollack’s mesmerizing delivery of this monologue—that it is only afterward, when we think back on it, that we realize that he hasn’t explained much of anything at all. His tale of orgies of the rich and powerful who will do anything to keep their secrets intact is essentially preposterous (although some of what he says may now ring uncomfortably true with some viewers in the wake of revelations about the late Jeffrey Epstein). Still, it is eventually enough to prod Bill out of his dream state and force him to face reality, especially in regard to his relationship with Alice.

This leads to the extraordinary final scene between Bill and Alice in the toy store, in which they genuinely communicate with each other for the very first time in what is, to be sure, a very long movie. The now chastened Bill apologizes to her. He asks her for advice—possibly for the first time—about how they should go about addressing the real and perhaps inevitable flaws in their seemingly picture-perfect marriage (which gains extra poignancy when you recall that Cruise and Kidman would themselves divorce less than two years after the film’s release).

It seems she is happy enough with this new attitude, claiming they are now both finally “awake,” but enough of a realist that when Bill claims that they will remain awake forever, she admits that such a concept frightens her. However, she does have an idea of how to begin their new period of being awake and attuned to each other. This leads to what I have already described as one of the great closing lines in cinema history—a single word that is hilarious and shocking in equal measure and the perfect one to close out both the film and, as would prove to be the case, Kubrick’s artistic legacy as a whole.

“Eyes Wide Shut” is a timeless and provocative work that forces viewers to interact with the ideas and conceits that it displays. Considering its challenging, uncompromising, and deeply personal approach, it’s unsurprising that it did not gel with viewers when it first came out. However, it has aged better than any other film from its era and feels as fresh and ambitious as ever—perhaps even more so in the increasingly timid cinematic times we live in. Whether you have never seen it before, wrote it off as a bizarre bore back in the day, or recognized its genius at the time, “Eyes Wide Shut” is an unforgettable work of art from one of the grand masters of the cinema—one utterly unlike anything he had done before. It will be seen, argued with and contemplated by anyone willing to take it seriously and embrace it on its own terms, as long as there are people around willing to see films as artistic expressions and not just IP extensions.

Oh yeah, it’s also a Christmas movie.

In the summer of 2021, U.S. forces completed their withdrawal from Afghanistan, 20 long years after the War on Terror began. By that point, though, most American had stopped thinking about that invasion, and as a result many never knew what happened after our military’s departure. In short order, the Taliban seized control of the country, leaving its future in peril.

Americans may have put that part of the world out of their collective minds, but others refused to forget, including Egyptian journalist Ibrahim Nash’at. Working at outlets such as Al Jazeera and Voice of America, he has interviewed world leaders, but had never visited Afghanistan. That is, until he journeyed to Kabul after the U.S. departure, convincing local Taliban officials to let him shadow them as they took over an abandoned base known as Hollywood Gate. Impressed with his résumé of covering political movers and shakers, the Taliban agreed to this unusual degree of access, hopeful that Nash’at would cast them as glorious victors. But what they and Nash’at found at Hollywood Gate shocked them, quickly realizing that the departing forces had left behind some of the estimated $7 billion worth of U.S. armaments that remained in Afghanistan, including military aircraft. We hadn’t just ceded power to the Taliban—in essence, we had helped arm them to the teeth.

“I went in thinking that my movie is going to be about how the Taliban finds the Americans’ shampoos,” Nash’at tells me over Zoom from Berlin, where he’s based. “I never expected this. My whole journey [was] a question mark of ‘How did this happen?’ And I hope that we can find a way of not making this happen again.”

To survive the harrowing experience of filming the Taliban, which lasted roughly a year, Nash’at had to make himself small, practically invisible, a nonentity. The resulting documentary, his first full-length feature, is “Hollywoodgate,” an unnerving piece of observational cinema that, as Nash’at’s brief voiceover suggests, attempts to do nothing more than present viewers with what he witnessed during his time with the Taliban at the base. There are no on-camera interviews, just a careful examination of how these military forces made themselves at home in this abandoned base and then began becoming accustomed to their new role as Afghanistan’s rulers, these men’s barbaric views on women on full display.

Because Nash’at and his subjects didn’t speak the same language, he needed an interpreter during filming. But it wasn’t the only challenge the 34-year-old faced while making “Hollywoodgate.” Below, the somber director discusses undergoing therapy, the benefit of not interviewing the Taliban, and why he doesn’t want U.S. viewers to forget their complicity in what has happened to Afghanistan.

How do you emotionally and mentally prepare for what you were going to have to endure? You were putting yourself in grave danger.

I really appreciate that question, and it’s important to talk about this, but I would rather talk about that this was a choice—me going to Afghanistan was a choice. I picked to spend time with the Taliban, but the Afghans never, ever chose to be in the situation where they are. The suffering and mental struggles and the therapy that I had to go through does not compare in any way to the daily suffering of the Afghans. So, really, I would rather keep the focus on the suffering of the Afghans rather than thinking about my own suffering.

All that I have to say regarding this topic is that I worked with [producer] Talal Derki from the first day. Talal did “Of Fathers and Sons,” and we got a lot of sessions of preparation, psychologically and mentally, of how I can spend a lot of time [with the Taliban]. We had a lot of conversations of how can one be prepared for nonexisting, basically, and not having to give his own opinion or take part [in] what’s going on around him. Of course, it was a lot of hardships, and I had to go through a lot of therapy.

What were the initial conversations like with the Taliban? How did you explain the kind of film you wanted to make?

I went to them when they were euphoric about winning the war. They were accepting so many journalists—they were trying to say, “We are Taliban 2.0. We are different.” I went in and I said, “I would like to show the world your image without putting my own point of view on it. Whatever I will see, I will try to show. I’m never going to make you heroes, I’m never going to make you villains—I’m just going to show what I saw.” I met with so many of them to be able to get access—everybody that I met, I always said the same [thing] for the whole year that I’m in there.

Sometimes, journalists have to be a bit ingratiating with their subjects in order to get them to open up. But that seems an especially fraught proposition when you’re dealing with the Taliban.

I understood that I’m in a military space, I’m dealing with military people—if there’s an order, you need to follow the order. The moment we got the access, whatever they would say, I would respect. So, if they say, “Don’t show the filmmaker that,” I would not try and go and see why they said, “Don’t show the filmmaker that.” Very rarely, I would break the rule—for example, the first time I saw the airplanes [in the base], I thought, “I’m never going to see them again.” They said, “Don’t film airplanes,” [but I] sneaked a shot because I expected that this is not going to happen again. Near the end [of the year], when I knew that I’m leaving, I started to take more risks.

Throughout the whole process, [they] were accepting the fact that I exist in [this space], so I never forced them to film when they were grumpy or annoyed. When I felt that I myself cannot handle it anymore—when I was feeling that this emotional fire is starting inside me—I would leave the country, go to Germany, do therapy, and come back again.

There was give-and-take of making them somehow miss me when I’m not there. I understood the power game that I’m following people who have ego. They wanted someone to follow them—they’re happy that this guy who films a lot of world leaders [is] following them. I was always playing on that, but I always let them understand that I’m just a follower—I’m not someone coming with a personality trying to prove anything. I’m just observing—I’m just in the room. And, of course, the language barrier helped me a lot to keep this distance.

During that year, did you get the sense that they came to like you or saw you as a partner in helping them change their image?

Some of them, they were hoping I would become one of them—they were trying to use their propaganda tools on me, hoping that I would take it and then I would transfer it. There was always this preaching to me about who they are. I never contradicted this with a harsh [reaction] of “What are you talking about, man?”—I was always saying [nonchalant], “Oh, okay.” I told them about this weird guy who was holding the camera: “This weird guy doesn’t talk much. Because of the language barrier, we cannot communicate much with him, so let him be.”

I became part of this new space they got into—they were also new [to] the base. I didn’t go to their caves—the caves were their village. They were discovering the [base] and trying to understand the space, and I was there—somehow, this worked out that I’m part of this new experience. When they started to understand how to become a regime and, “Oh, this guy might be dangerous,” [filming] started to be very hard. But I was already inside [the group], so if they kicked me [out], I would talk to other people to return to where I was.

When you would go back to Germany for therapy, did you ever worry the Taliban wouldn’t let you back in?

It happened many times. At the beginning, I had a longer visa, but every time you leave, you have to renew your visa, so it started to become harder. Sometimes they said, “No,” so I had to try to talk to other people, and then one person said, “Yes,” and that person said to the other one, “Yes”—I would make them talk to each other. It was always a constant fight to make sure that I would come back.

You spend a lot of time filming Mawlawi Mansour, a Taliban leader who’s just become the new head of Afghanistan’s air force. Putting aside his worldview, did you think he was actually an effective leader?

I think he was trying to become one. I could see the people gathering around him, but at a certain moment he understood the amount of power he has and he started to slap people around, liking the fact that then they would kiss his hand. In the beginning, I saw him trying not to be [like] the [opposition forces] he was fighting, but I saw him becoming the ones he was claiming he was fighting. I saw this process happening in front of me. [Initially] he was nice and smiley and talking to people of lower ranks—and then started to be more distant, more distant, more distant.

What happens to leaders of the Taliban regime? The people around them do everything for them, and then they sit in their office: “They want me to sign here,” and he signs there. If the leader signs papers without reading them, I don’t know if I could call him a good leader. Yet, people would still follow him. He understands the tools he’s got—the power of religion, the power of [the] military, and a lot of power that makes him know that people will follow him anyways.

Everybody gets corrupted. Power is much stronger than any human being. What keeps the system in the U.S. working is that the Constitution is still holding up. At the moment someone is capable of breaking the Constitution, then you see dictatorship—easy.

What has been the response from American viewers to your film? It seems to me that many in my country want to forget our involvement in Afghanistan—we want to pretend that failure never happened.

The people who watched [the film], they want to make sure that they were reminded of the fact that the U.S. did this, reminded of what happened there so this [will] not happen again. Foreign policy should change, not allowing the U.S. to conduct such wars that would [lead to] such outcomes. Those who hope that the future is brighter and the mistakes are not going to be repeated want to make sure that this [film] is seen by every decision-maker to make sure that the Constitution is not allowing something like that to happen.

Those who just want to forget because it’s painful to understand “We [made] a mistake” is pretty much what the Taliban does as well. In the movie, [the Taliban soldiers] lost all of the medicines [at the base], and I stayed for three days waiting for them to talk about “How did we lose these medicines and how can we avoid such a mistake to happen again?” They never spoke about it. When totalitarian regimes do something good, they talk about it so much—when they do something bad, they try to bury it. If the system in the U.S. is following that [tendency], this is a big question mark—this is purely against the idea of democracy.

During filming, did you find any answers to why the American military was so thoughtless in leaving behind all these weapons and equipment for the Taliban? We must have known the Taliban would take it all.

The bigger question is, “Why did you go there [in the first place]?” I expected that I was going to do a movie to show the world in whose hands this country was left. I wanted to show the world that the U.S. and NATO left the country to the Taliban. I know that the media tends to forget because it’s not a hot topic anymore, and it becomes repetitive, so I want to make something to bring back the story of the Taliban and Afghanistan [to people’s attention] so we don’t forget them like so many places that were forgotten. This was my mission, but all of these weapons were, let’s say, a gift to make [my film] more interesting.

I imagine many will see “Hollywoodgate” because they’re curious about what the Taliban’s seizure of this base looked like. But they’ll also notice the glaring absence of the U.S. military—you only see the weapons and the personal items that soldiers left behind. And that absence is damning.

This is a movie about antagonism from both sides, and the only hero in this are the people who are suffering. We don’t see American soldiers in the film [but] we feel the presence of the Americans. We don’t see the [Afghan] people [but] we feel the presence of the people. When you put a couple of images back to back, they convey way more than what you see—this is the beauty of observation in cinema.

Because you spent so much time with the Taliban, did their behavior or attitudes ever become normalized for you?

It’s a coping mechanism—you wish to forget who you’re dealing with so you can have less trauma. This, I learned in therapy—at some point when I went to Berlin, I told the therapist, “Hey, I’m having Stockholm syndrome,” and she said, “No, that’s not Stockholm syndrome, you’ll have Stockholm syndrome later. That is just normal—you’re trying to find the similarities to live your day. If you get too close, just ask ideological questions.” Which was a brilliant suggestion. If someone offers you a brilliant meal, you [might think], “Oh, this food is great, I like you already,” but then I would directly put out an ideological question: “What would you do if your daughter wanted to become a judge?” Then they would open their mouth and say every single word that builds back the distance and reminds me of whom I’m dealing [with].

There are no direct interviews in “Hollywoodgate.” Were you ever tempted to utilize those?

I’m a big fan of observational cinema. I’m a big fan of Frederick Wiseman films—he’s my idol. I’m very happy—he came and saw the film [at the Venice Film Festival], and he liked it, which was the top of my career.

For me, a movie should not have voiceover and should not have interviews. If you have to do this, it’s one point less somehow. But also, I discovered that not doing interviews [with the Taliban] was another way of protecting me, because if you do interviews and you talk more, they understand what’s in your head through your questions and what answers you’re trying to get. Not asking questions—not coming close with interviews—was also a protection for me, which I didn’t realize then.

Once you spend your year with them, how do you find the film in the edit?

We tried to create a Shakespearean drama like “Macbeth.” I tried to make sure that I don’t make another “Godfather,” because “Godfather” has this backlash of being a positive movie. But when we sat down to edit, we said, “This is not ‘Macbeth,’ because Macbeth ended horribly—he died. But [Mansour has] a parade. How can you make a movie like that?”

We found, finally, the best way [to put together the film] is to use my story—which I was refusing in the beginning to have at all—as the tool that leads the story. It opens the story, it ends the story—we just put the viewer in the place of the cameraman.

Of course, you can’t fully convey what it felt like to be in that abandoned U.S. base. Is there something you learned from being there that we don’t see in the movie?

What I experienced [but] didn’t serve the story is that I went through the books in the soldiers’ rooms. Most of them are about trauma and pain and therapy, which directly put me in the understanding that the pain is the same. Everyone here was feeling pain because it was war. War is just making everybody suffer on both sides—this was something that was really, really heavy on my shoulder.

Making this film, what was the ratio of sadness to anger that you felt? Both feelings are legitimate, of course, but what was your mindset most of the time?

I’m not an angry person in general. Maybe I was raised in a way that I think anger is a [bad] feeling—I learned through [this] process that it’s not, but also therapy taught me that. Most of the time, I was sad but, really, I was confusing the idea of being angry by only being able to express it as sad, because angry is a negative emotion and sad is an acceptable emotion. Before therapy, I could not know the difference—both of them were one thing to me, expressed as one thing: sadness.

You made it through this experience, but I worry that “Hollywoodgate” is just another reminder that war is never-ending. The Taliban will keep fighting—the U.S. and other nations will as well. It’ll never stop.

This was my thought. One thing that I could not move past is the obscene power of those who worship war. And by that, I don’t mean only the Taliban—I mean anyone who worships war and the pain that they caused for generations. We keep paying the price of that. You see the world today, everybody’s just paying the price, everywhere.

I don’t remember a time in my life where I wasn’t aware of who Richard Simmons was. As a child of the ‘80s and ‘90s, the flamboyant fitness guru, who seemed to be an endless fount of energy and joy, was everywhere in the media. He was on talk shows. He was in magazines. He was in commercials. He was on game shows. He was even in an episode of “Rocko’s Modern Life.” But more than that he was a guiding light for people like my mother.

She has struggled with her relationship to food and to her body most of her life. As a kid I remember her trying every kind of fitness fad and diet, from Tae Bo to Atkins, but the one constant was the Richard Simmons “Sweatin’ To The Oldies” workout tapes. I myself have never been a big fan of working out, even as a little kid, but I always did the tapes with my mom. She even gave me the DVD set released by Time Life ages ago. I still pull them out and do them to this day.

What made them different and what caused so many people to return to them over the years was the fact that Richard Simmons made working out fun. His workouts were set to jukebox classic pop music from the 1950s and 1960s like “Jailhouse Rock” and “Dancing in the Street.” The people in his videos were his own students and they were every body type and shape. At the end of every video there would be a dance circle where each cast member got to show off their moves and how much weight they lost or if they had just started on their journey.

But even with this emphasis on weight loss at the end of each video, it never felt like weight loss in and of itself was the goal for Simmons. It was embracing fitness and finding ease with your body. There was no “feel the burn” mania. Just simple dance moves that helped you connect with your limbs while feeling the beat. He would look directly into the camera and tell you that you could do it, but if you needed to take a break there was no shame. Do what you can. Work up to it. Fitness should be fun, not a chore.

Simmons’ journey towards becoming a fitness guru was as wild and weird as the man himself. Born Milton Teagle Simmons in New Orleans, Louisiana on July 12, 1948, Simmons was raised in the French Quarter, amongst a “show business family” – his father worked as a master of ceremonies and his mother was a traveling fan dancer. Later his parents turned to business, working in thrift stores and as a cosmetics salesperson. All of this, it seems, Simmons synthesized into his own larger-than-life persona and savvy business acumen.

According to Simmons himself, he struggled with overeating as early as four years old, and by the time he was in his twenties his large frame led to background roles in Fellini’s “Satyricon” and “The Clowns,” which he filmed while he studied art in Florence. After he went on an unhealthy crash diet to lose the weight, he moved to Los Angeles in the 1970s where he opened his eccentric exercise studio and salad bar restaurant known as Anatomy Asylum and Ruffage, which focused on teaching people healthy eating and portion control and was said to be frequented by celebrities like Paul Newman, Diana Ross and Barbra Streisand.

After a series of appearances on talk shows – and even a stint as himself on “General Hospital” – Simmons began hosting a humorous half-hour exercise show called “The Richard Simmons Show,” which at its peak aired in 173 markets across the United States. The show aired from 1980 to 1984, earning several Emmys along the way. His breezy irreverence and sometimes self-deprecating humor about his own lived-in issues with food was a stark contrast to the perfectly sculpted fitness gurus that came before him. Dubbed “the clown prince of fitness,” he was approachable and therefore he made fitness approachable.

The first “Sweatin’ to the Oldies” tape dropped in 1988 and immediately became a bestseller. Over the next few decades, Simmons would release countless more tapes, wrote a dozen books, and could still be found teaching classes at his exercise studio, renamed Slimmons, almost until it closed in 2016. He also embraced the internet, usually the power of social media to continue spreading joy and compassion and helping people on their own fitness journeys.

Simmons passed away on July 13th in his home in the Hollywood Hills, apparently of natural causes. He was 76 years old.

I heard about his death from my mother, who called me as soon as she heard the news. She was overcome with grief. However, while talking to her about him, her sadness shifted to a joyful remembrance of the time we spent doing his tapes together and the confidence he had instilled over the years. By the end of our conversation, she was left with nothing but the overwhelming feeling of gratitude.

Over the decades, Simmons would reach out to fans via email, social media, and even the phone to offer words of encouragement. In fact, about 15 years ago, the night before my mother was going to participate in a three-day breast cancer walk, the phone rang and Simmons was on the line. He asked how she was doing and she told him about the upcoming walk and how she wasn’t sure she could do the whole thing. He just laughed and told her to go as far as she could and then take the support vehicle the rest of the way. You can do it, but don’t strain yourself and don’t feel ashamed if you need to take a break.

It’s this kind of deceptively simple piece of advice mixed with positive encouragement delivered with a little bit of razzle dazzle that Simmons specialized in. We all need to hear it from time to time. Simmons knew it well. Like so many of his fans, I will miss his positive energy. But, like my mother, I will always be grateful for it.

In his latest movie “The Convert,” director and co-writer Lee Tamahori returns home to New Zealand for a look at a fraught chapter in the country’s history. Bringing his action movie bona fides from the James Bond entry “Die Another Day” and “xXx: State of the Union,” Tamahori hews intense dramatic moments over battlefields and tense conversations as two factions of indigenous Māori wrestle for control while British colonists set up one of their first claims on the nation. Our main character enters these most turbulent times advocating for peace and finds few listeners. This is not an uncommon chapter in history, but the way Tamahori and his cast and crew approach the topic is fascinating, even if sometimes a little conflicted.

In 1830, Thomas Munro (Guy Pearce) lands in New Zealand. After years in the military, he’s a troubled man who wants to get away from England as much as possible and finds passage to the other side of the world as a lay preacher. However, our adventurer does not find peace. Instead, he finds a community in tumult as two Māori chiefs, Maianui (Antonio Te Maioha) and Akatarewa (Lawrence Makoare), fight among themselves for control of the region, traders like Kedgley (Dean O’Gorman) supply muskets and bullets to both combatants and the British colonists in the town of Epworth ostracize anyone not British and Protestant. They even go so far as to withhold medical supplies from a wounded Māori woman, Rangimai (Tioreore Ngatai-Melbourne), whom Thomas rescued from an ambush. As tensions mount, Thomas finds allies with Rangimai and a widow named Charlotte (Jacqueline McKenzie), even as war seems all but inevitable.

Thomas feels like something of a Trojan Horse character, an outsider to interest audiences beyond New Zealand in its history and a perfect excuse for constantly translating different languages and customs. However, something feels missing from his character, even if he has the most screen time to share his past war stories and beliefs. Pearce brings him to life with the most solemn of performances, quietly restraining his emotions – and violence – until the very end. But his story isn’t the most compelling.

The real heart of the movie belongs to Rangimai, a woman tormented by the violence of the men around her yet more than willing to take her revenge for the murder of her husband. In a star-making turn, Ngatai-Melbourne rises to the occasion with her bold performance, singing funeral songs for the dead, taking up arms against her enemies, yet also sharing rare scenes of tenderness with Charlotte and Thomas. The character is secretive yet earnest, understands the political games at play, and is willing to participate in its events. She’s eager to learn from her British neighbors even as they reject her and her people because she understands that to know them is itself an advantage.

Tamahori and co-writer Shane Danielsen may have taken some historical liberties in loosely basing their script on true events, creating composite characters or writing in new figures. Still, if the goal of “The Convert” was to give a sense of New Zealand when most of its residents called it by its Māori name, Aotearoa, then it is successful. Cinematographer Gin Loane frames Tamahori and Danielsen story with the gorgeous natural landscape around them, sometimes shooting in stark contrast to show off the dark sandy earth, inky rivers, and cloudy skies. In other moments, the camera revels in the crashing white waves, formidable rocky cliffs, and luscious green forests, occasionally moving in to focus on a bird or plant, grounding its story with a sense of place like no other. Thomas sees this part of the world for the first time, and the camera mirrors his curiosity. Likewise, the visual style is also used to heighten the narrative’s more dramatic scenes, like when Rangimai greets her father, the chief, after the murder of her husband. The reunion happens near the coastline, where the soil is dark, and the skies appear stormy, a harbinger for the battle forecast ahead.

“The Convert” is Tamahori’s third feature set in New Zealand. His breakout film “Once Were Warriors” introduced him to international audiences, and decades later, he returned with “Māhana,” a period piece following a Māori family in the 1960s. This trip back in time for “The Convert” is perhaps one of the more ambitious titles in his filmography, one painstakingly researched for accurate details to recreate Māori homes, costumes, and dialect, stocked with numerous extras and supporting characters to bring the last of the country’s pre-colonial days to the big screen. In that sense, the movie takes on a bittersweet note, bringing history to life in all its messy complexity – and the everyday players who shape it.

If he’d only ever been a cinematographer, Jan de Bont would have had an impressive career. Working with Paul Verhoeven, Richard Donner and Ridley Scott, the Dutch cameraman helped lens some of the most memorable action films and thrillers of the 1980s and 1990s. (Two of the best movies of that era, “Die Hard” and “The Hunt for Red October” were shot by him.) But in the early ‘90s, shortly after filming “Basic Instinct,” he made the leap to directing, his debut the now-classic “Speed.”

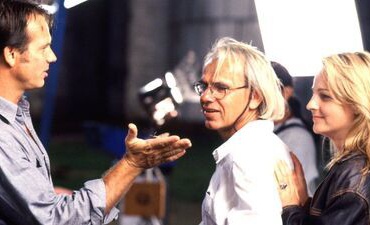

De Bont followed up that commercial and critical success with 1996’s “Twister,” a fun romp involving former storm chaser Bill (Bill Paxton) reluctantly tagging along with his soon-to-be-ex-wife (and fellow storm chaser) Jo (Helen Hunt) to track down a massive tornado. Bill needs Jo to sign the divorce papers so he can move on with his life—and marry his uptight fiancée Melissa (Jami Gertz)—but she’s too obsessed with this once-in-a-lifetime storm to focus on something so menial. (Plus, spoiler alert: Bill and Jo are still secretly in love with each other.) Amidst deadly winds, these two will rekindle their romance—depending on your perspective, “Twister” is the most expensive screwball romantic comedy ever.

“Twister,” which was the first theatrical film released on DVD, was a huge hit, and now it’s coming to 4K Ultra HD disc and digital. With “Twisters” about to land in theaters, it felt like a good time to talk to de Bont, now 80, about his film. But he also wanted to discuss the action-movie climate in which he came of age as a cinematographer. “In the ‘70s and ‘80s, those movies, everything was about those one-liners,” he says disparagingly over Zoom. “It drove me crazy because none of [those one-liners] were really funny—they were just a written sentence that quite often had nothing to do with the story, and it really annoyed the hell out of me. I worked on movies like that.”

Still, de Bont was committed to ensuring his own films were fun and funny—who could forget the infamous “Twister” scene involving a flying cow? I asked him about that, and also what it was like to work with a young Philip Seymour Hoffman, who played one of Jo’s colleagues. He also had thoughts about real-life storm chasers, modern blockbusters, and what he values in an action movie.

Rewatching “Twister,” I realized we don’t often have action movies these days that are also love stories. That’s true of this film but also “Speed.” Was building a romance into the narrative important to you as a director?

Anytime you can put regular human emotions in a movie, it makes people more aware that these are real characters. I like subplots that don’t always come to the foreground, but each time that little infusion makes the characters more real. I mean, [Jo] talks nonstop about science, but it’s nice to see her really have an argument about signing the [divorce] papers—that is such a simple thing, [but it’s] so great, so human. It doesn’t have to be a grand love story, like “Titanic”—[it can be] more regular.

When you made “Twister,” how concerned were you about the science being accurate? You didn’t stress out about that since you wanted to create a fun, escapist summer movie.

It is supposed to be fun, absolutely. But viewers have seen tornadoes on TV, so I felt that I have to make them look real. Otherwise, [it] would distract from the reality of the terror that they create—if you don’t make them real, then you don’t believe the rest.

We worked a lot with not only storm chasers but Severe Storms Lab in Oklahoma, and they gave me so many movies and photographs of all different [storm] events. I ended up using a lot of that: If they happened for real, then they would be good for the movie. We had scientists on the set all the time—we had two storm chasers, we had two weather forecasters—for safety for the whole crew. It was nice talking to them—they became part of the crew. They knew all the lingo that exists about weather and storm-chasing.

I didn’t want to invent things—although, the cow is invented. Well, halfway-invented, because I saw a picture of [a] cow in a tree, which I thought was fake—and then they said, “No, it’s real.” I said, “Okay, we have to put it in the movie.” I started thinking, “Wow, wouldn’t it be great to see that cow flying through the air?” But I said, “Yeah, but just flying through the air, that’s kind of meaningless. If you see it from a car and you suddenly see [it] flying by, that’s much funnier because then there are people to react to it. Otherwise, if you see an abstract shot—‘Oh, cows flying’—that’s definitely not funny. You’re saying, ‘Oh, poor cow.’” Now, nobody says, “Poor cow.” They are saying, “Oh, funny cow.”

Back when “Twister” came out, storm chasers weren’t as big in the culture as they are now. What were the real-life storm chasers like that you met?

We got to understand their addiction to adrenaline and danger. But, also, those guys are weather nuts—they really photograph everything, film everything, and a lot of this stuff goes to the Severe Storms Lab. What they have fun doing, they want others to profit from it—I had no idea.

There are a lot more of them now. I think there are tour groups now for storm chasers, which is kind of silly to do as a tourist, but they do happen. But I think it’s also that, despite all the incredible improvements they have made in depicting tornadoes, they’re still deadly and they still come every year and destroy towns, farms, and trees. Nothing has really changed. So I think the chasers will be more visible, and I think that people [in tornado areas] will be more interested in weather than they ever were before because their life depends on it.

You didn’t grow up in a place with tornadoes. What was your first experience with a twister?

During the making, we [saw] some tornadoes, especially in pre-production, and they’re scary. They were actually more scary than I thought they would be. I always thought, “It looks so pretty, they move through the landscape…,” but when you get closer, they’re not so beautiful. And when you see the destruction, they’re really pretty bad.

You worked with the late Philip Seymour Hoffman before he was a household name, before he won an Oscar. His character Dusty is the film’s comic relief, a very different type of role than he would later play.

He was the last actor I cast. The casting director showed me some clips, but I was ready to focus on the movie [so] I really didn’t pay that much attention. [At the audition] I immediately liked how he sat in his chair when he entered the room, exactly like you see it [in the movie]. Really relaxed, laid back. [Jan de Bont imitates Hoffman’s character’s sitting style.] And I said, “That is Dusty.” The way he was dressed, the sloppy baggy pants and open shirt—I said, “Man, did he dress for the part?” I still don’t know, he never told me. It was so funny that we then ended up using that outfit for the movie—we just made duplicates of it.

He was an amazing character. He gave a lot of peace to the whole group. He’s calm, he was lighthearted. He could make a little joke about things that would smooth things out, but he also could go emotionally the other way. We started writing more scenes for him because there were not that many scenes in the movie [for him initially]. Basically, he helped to create his own role and increase it, making it a lot better.

This was your second film as a director after working as a cinematographer for years. I’m impressed by how confident you were in making blockbusters that were funny—these big movies had a light touch to them.

I absolutely knew that comedy, a lighter tone, was really important. It’s not the first time: When I was still working in Europe, in Germany, I was working on a TV series, which was basically the German version of “Monty Python’s Flying Circus.” I did a lot of episodes and I totally loved it.

People cannot underestimate what a few lighter moments can mean in a movie—it’s really, really, really key. And make it entertaining because, really, movies are entertainment. How can you make it entertaining and also be good at the same time—and exciting? The combination of that is harder to achieve—you have to work hard for that. But if it works, it works.

Your films were relatively small-scale. Nowadays, blockbusters have much bigger stakes than your films did: The planet is in danger, or maybe even the galaxy.

I wouldn’t want to make those movies. I wouldn’t be interested. By creating these lower expectations, you’re making it much more accessible for an audience. By keeping it on a smaller scale, I think an audience doesn’t have to work so hard to imagine a universe. If you make the scale so big, it loses your interest because you don’t want to invest all that time thinking about “How the hell does that happen? How does that world exist?” It’s just not worth it.

I want, honestly, to have two hours of a really good time. It’s really to be excited, to be able to smile once in a while, to get emotions out. Don’t make it so big that [it] becomes ridiculous. You don’t want the whole city to come down [in “Twister”]—would that make a better movie? Absolutely not. It’s much better to see the effect on one farm, one family, than on the whole city. It becomes immediately abstract when you do it that big. I want it to be personal. I want it to be connectable. I don’t see me doing anything different.

[Ominous announcer voice:]

“This is a video about the 1974 motion picture ‘The Parallax View,’ featuring a discussion of the film by Matt Zoller Seitz and ‘Mr. Robot’ creator Sam Esmail, edited by Nelson Carvajal. This video analyzes the entire movie, its script, editing style, cinematography, and themes, and the genre of the paranoid thriller that it’s part of. It should be viewed after watching ‘The Parallax View,’ not before.”

“This concludes our warning. If you have accepted the terms under which this video is being presented, press play now.”

[LIGHTS DIM; VIDEO STARTS PLAYING]

Many of my favorite films have endings that most people would consider unhappy. But I don’t. To me, the only ending that makes me unhappy is the wrong ending. “The Parallax View,” the 1974 paranoid thriller starring Warren Beatty as a renegade reporter investigating the murder of a United States senator, has the right ending for the story it presents—the kind of ending that fills you with dread and despair, but might also make you laugh (bitterly, and with admiration) at its audacity.

The beginning and middle of the film are great, too. And right around the halfway point is a montage that I consider one of the finest demonstrations of the essence of film editing since the Russians of the 1920s stitched unrelated shots together to see if it alchemized feelings and meanings the shots could not convey in isolation.

Beatty’s character, Joe Frady, is a recovering alcoholic with anti-authoritarian tendencies. He lost his job as an investigative reporter at a Seattle newspaper and only recently got it back, but is now in danger of losing it again. It is implied, not directly stated, that part of Joe’s problem is that he’s traumatized by the events in the film’s opening sequence, the assassination of the Senator during a party in the restaurant atop the Space Needle. (It’s staged to evoke the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy in Los Angeles six years earlier, as well as the killings of JFK, MLK, Malcolm X, and other leaders.) Everybody in the film’s potential audience was traumatized by the instability of that era. “Parallax” spoke to some of the worst of it.

This was a time when, paraphrasing one of Joe’s lines, it seemed as if every time you turned around, somebody was knocking off a leader or trying to. Two years before “The Parallax View” came out, President Richard Nixon survived two assassination attempts, one of which ended with would-be murderer Arthur Bremer wounding independent presidential candidate George Wallace. A month after “Parallax” came out, a disturbed man named Samuel Byck tried to kill Nixon by hijacking a commercial airliner and crashing it into the White House. Somehow, the authorities always concluded that the killer or would-be killer was a mentally or emotionally disturbed person who had acted alone. After a certain point, that stock conclusion began to seem both chilling and absurd. The coda to the opening murder captures ’70s skeptical ennui perfectly: A Warren Commission-like body of judges releases the results of their investigation into the senator’s murder, which concludes that the killer acted alone and “there is no evidence of any wider conspiracy; no evidence whatsoever.”

Well, of course there’s a conspiracy. Joe doubts one at first. But then his friend Lee Carter (Paula Prentiss), a TV reporter who was also at the Space Needle that day, shows up at his apartment to warn him that many witnesses to the killing have died suddenly of supposedly ordinary causes, then ends up dead herself. Joe starts digging with the reluctant approval of his editor (Hume Cronyn) and becomes convinced that the assassinations are the work of The Parallax Corporation, which he believes is a front for an operation that scouts, recruits, and trains contract killers. Joe’s plan is to convince the corporation that he’s the perfect candidate for training, then infiltrate the company and expose the truth. Things don’t go as smoothly as he’d like, partly because Joe is a hot-tempered, impulsive, chaotic person who causes an epic scene wherever he goes. But what if this makes him exactly the kind of person Parallax wants to recruit?

The question recurs again and again at high velocity in a sequence that fans call “The Incredible Montage”—a psychological test shown to would-be Parallax recruits. While a four-minute, alternately upbeat and martial-sounding bit of music plays, Joe sits in a large chair festooned with testing equipment and watches a series of tightly edited still images interspersed with white-on-black text flashes of single words (ME, HAPPINESS, MOTHER, FATHER, GOD, COUNTRY). The same images are repeated and sometimes cropped or flipped and placed before or after the words as they repeat.

The result is the video equivalent of a written screening test found by Joe earlier in the movie. The test poses the same questions repeatedly in different words, presumably to short-circuit the guardedness or deceptive intentions of people like Joe who are trying to perform the type of personality they think Parallax wants rather than reveal the one they actually possess.

One of the film’s masterstrokes is rewriting the montage sequence to exclude previously scripted closeups of Joe reacting to the montage. The absence of reaction shots of Joe makes us feel as if we are Joe. We’re sitting in that chair and thinking about how the images make us feel. Maybe we’re trying to will ourselves into feeling a particular way and figure out why certain images were chosen and placed in certain spots. We’re doing our best to control whatever is happening, but we’re doomed to fail. The images move so quickly that staying intellectually detached from what you’re watching is impossible. At some point, you give in and ride the flow of the pictures and music, feeling whatever you happen to be feeling at any given second, which is the point of a test like this.

The crew of “The Parallax View” includes some of the most original film artists of that decade, including two of Pakula’s most trusted paranoid thriller collaborators, cinematographer Gordon Willis (who also shot Francis Coppola’s “The Godfather” and “The Conversation,” among other 1970s classics) and composer Michael Small; and screenwriters Lorenzo Semple, Jr. (“Batman,” “King Kong”) and David Giler (“Alien“), with uncredited, on-set rewrites by the recently departed master script doctor Robert Towne.

The result seems like one of those miraculous productions where everything seems carefully conceived and methodically executed, even though reports of the film’s production confirm that there was a lot of drastic rewriting of both Loren Singer’s source novel and various screenplay drafts, as well as some in-the-moment creative decisions that caused great rancor on set. For instance, while shooting a scene where Beatty had to convince a bad guy that he was a dangerously violent man, Willis secretly decided to keep the star’s face in shadow to ensure the scene would work even if Beatty’s acting wasn’t good enough. Willis’ assistant later said that the ensuing behind-closed-doors conversation between Willis, Pakula, and Beatty was the closest Willis came to getting fired from a movie. The face-in-shadow takes of Beatty ended up in the movie, and they’re brilliantly right, just like everything else in the picture.

You’ve heard of a downer ending? More specifically, you’ve heard of a 1970s-style downer ending? This one has one of the downer-est endings ever. But it’s one of the greatest and most correct endings of any film. Its ruthless commitment to the truth of the film’s bleak vision of life is thrilling and cathartic.

Watch “Parallax” once, and you’ll be mesmerized and made to think. Watch it again, and you’ll appreciate the simplicity and efficiency of the film’s construction. It’s the movie thriller as sniper rifle.