Jane Giles and Ali Catterall’s documentary “Scala!!!” is about a legendary, notorious, hugely influential and long-gone London theater. But it’ll appeal to anyone whose formative moviegoing years were defined by eccentric, usually urban or college-town cinemas that programmed whatever the folks who ran the place found interesting and switched lineups every day or two. There are increasingly few such venues left, alas, with real estate having become usuriously priced all over the world and “content” having largely replaced the notion of “entertainment,” a thing one sought outside of the home. Witnesses to the Scala’s history include patrons, management and staff, many of whom were or became notable filmmakers or programmers, including John Waters, Ben Wheatley, Ralph Brown, Mary Harron, Beeban Kidron, and Isaac Julien.

The thrill of transformation is a subtext. The Scala didn’t just show films, it stimulated interest in cinema, challenged and offended viewers (on purpose), and pushed the limits of what was then considered acceptable to screen in England. It championed pro-union and LGBTQ-friendly films, early works by subsequently legendary directors (including David Lynch’s “Eraserhead”), and underground movies that blurred arthouse and grind-house categories. One of the more fascinating tales is about the durable appeal of 1975’s “Thundercrack,” American filmmaker Curt McDowell’s fusion of an “old dark house” movie, a surrealist art flick, and a hardcore porno. “It was screened at the Scarlet constantly, probably from the day the cinema opened right to the time it closed,” says says Alan Jones, co-presenter of London’s Shock Around The Clock horror festival at the Scala, and one of the film’s most entertaining interviewees. “Legend was that there was only ever one print of Thundercrack here at the Scarlet, and it was run until eventually it fell apart.”

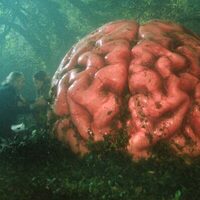

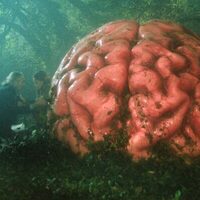

Located in the King’s Cross neighborhood of London before it became gentrified, the Scala started out as a traditional theater, closed and reopened, and then for 15 years was essentially a film club catering to buffs of one sort or another. During the later era, the film’s focus, it was a “ground zero” locations for the budding fan culture scene in the UK, popularizing John Waters “trash” trilogy of “Pink Flamingos,” “Female Trouble” and “Desperate Living” and films by Russ Meyer, and hosting the first Avengers convention, meetings of The Laurel and Hardy Appreciation Society, and The Shock Around the Clock festival (described by critic Kim Newman as “Kind of like Woodstock for the bizarro generation”).

The venue always struggled to keep its doors open but eventually succumbed to a variety of adversities, including rising costs, a siphoning away of repertory and art house viewers by home video. At the end, the killing blow might’ve been a lawsuit from Warner Bros. that was filed after the theater decided to disobey Stanley Kubrick’s decision to pull the film from UK distribution after what appeared to be copycat killings; after the Scala Film Club lost the case, it went into receivership, and while it reopened in 1999 and added two floors, it focused on live entertainment.

Non-obsessives may find a lot of the movie incomprehensible because so many of the titles and artists mentioned in it are more than 40 years old, but also because the era described is pre-digital. There’s a lot of comfortable shop talk about the physical processes of making and exhibiting the physical object known as “a film,” which had to be carted around in canisters and stored and handled properly so it didn’t break or catch fire. “I was always maintained that the Scarlet was willing to screen any length of celluloid that had half a dozen intact sprocket holes,” says Jones. “Because of that, the films tended to break.” They also sometimes tore, stuck in the projector gate and caught on fire, a frightening but literally luminous occurrence that the movie describes with a fair amount of reverence, even cutting editorially to a bit from the Peter Fonda film “The Trip” where the actor exclaims, “It’s like an orange cloud of light that just flows right out of us!”

Based on Giles’ 2018 book Scala Cinema 1978-1993, this documentary remembrance is so enthusiastic that it can get exhausting, like listening to a lovable but manic and inebriated friend go on about his favorite stuff until the sun comes up (which, to be fair, is surely a stylistic feature rather than a bug; the Scala was known for its all-night marathons). But at a time when unabashed enthusiasm for anything is labeled “cringe,” it’s a treat to see so much energy expended to recall a venue and a community that was unknown to most, but felt like the center of the universe to the merry few who were part of it.