Daihachi Yoshida’s “Teki Cometh” is the first Japanese film in 19 years to win the top prize at the Tokyo International Film Festival. The win reflects a feeling of optimism that pervaded this year’s TIFF, as Japanese theaters bounce back from COVID-era lows and Japanese filmmakers like “Drive My Car”’s Ryusuke Hamaguchi and “Godzilla Minus One” director Takashi Yamazaki receive accolades abroad. Yoshida has yet to gain that kind of international recognition. But “Teki Cometh,” a darkly comic character study about an aging professor whose orderly life is upended by a series of terrifying spam emails, makes for a fine ambassador.

Yoshida broke out nearly 20 years ago with his 2007 film “Funuke, Show Some Love You Losers!,” a dark comedy about a narcissistic wannabe actress and her emotionally abusive relationship with her manga-artist sister. Sumika (Eriko Sato) is a less sympathetic character than “Teki’s” Professor Watanabe (Kyozo Nagatsuka) — Watanabe is deliberate and considerate, if a bit oblivious to how the world is changing around him. But Yoshida observes both of them with patience and compassion, creating fully fleshed-out characters with histories and motivations and fantasies and emotional lives.

The same is true for all of his characters: Take Yoshida’s 2014 drama “Pale Moon,” a fable about greed set shortly after Japan’s economic bubble dramatically burst in the early ‘90s. In that film, bank teller Rika (Rie Miyazawa) is tempted by both easy money and an extramarital affair. She makes some questionable decisions under the influence of both, but she and her much younger paramour are both depicted as complicated, confused people who are doing their best — a decision that makes the film exponentially more engrossing and thought-provoking.

All three of those films are based on novels. Most of Yoshida’s films are, which helps account for their complex characterizations and expansive inner worlds. “What I try to be very deliberate about is to translate into film how that novel made [me] feel right after [I] read it,” Yoshida says. “Teki” is based on a book by Yasutaka Tsutsui, the novelist whose works also inspired the films “Paprika” and “The Girl Who Leapt Through Time;” after “Teki’s” world premiere, Yoshida joked that his personality is “70 percent” derived from Tsutsui’s work, a figure he says is exaggerated but “not a complete lie” in our interview.

A voraciously curious, self-motivated artist who at one time wanted to be a punk rock musician — he’s currently studying under a Noh theater master, simply because he finds the discipline interesting — Yoshida says he admires Tsutsui for confronting taboos in his “politically incorrect” novels. “Reading [Tsutsui’s] work, you’re very aware that there’s no limit to the imagination. And we are very, very free in our imagination,” he says. “That seed was planted in me at a young age as I was reading his work. And for that, I’m very thankful.”

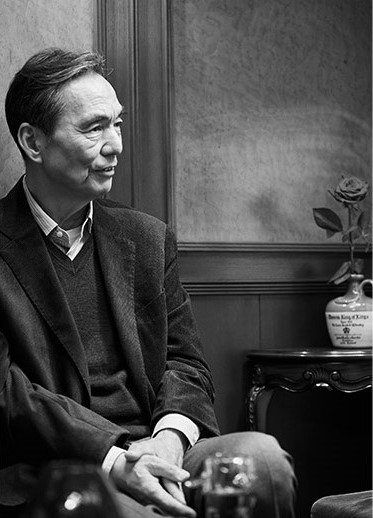

Yoshida read Tsutsui’s book “Teki” — Japanese for “enemy” — nearly 30 years ago, and revisited it during the COVID shutdowns of 2020. “It hit closer to home the second time around,” the director, currently 61 years old, says of the novel. “There were details where I was like, ‘oh, that happened to me yesterday.’” The story begins by following Watanabe through his modest daily routine as a retiree living in his family home, a traditional Japanese-style house with a dried-up well out back and decades’ worth of memories piled up in the shed.

The film was shot in an actual, occupied 100-year-old wood-and-tatami house, with an aesthetic inspired by classic Japanese films like “The Sound of the Mountain” from director Mikio Naruse and Yasujiro Ozu’s “Late Spring.” “You can’t imitate what Ozu did, of course,” Yoshida says. “But it served as good motivation to be reminded once again how beautiful a Japanese house can be.” Then, over the course of 108 minutes, Professor Watanabe’s tidy reality disintegrates, as he starts receiving — and then, more crucially, believing — messages warning him of an unnamed “enemy” coming from the north.

That’s when another, more recent reference comes into play: Part 8 of “Twin Peaks: The Return,” whose coal-smudged “Woodsman” served as a visual reference for Watanabe’s dreams of an encroaching “enemy.” At the film’s world premiere in Tokyo, Yoshida rejected the idea that “Teki” and “Teki Cometh” depict the onset of dementia, saying that the film’s seamless shifts between fantasy and reality are open to multiple interpretations. They’re also laced with dark humor, some of it quite scatological: “If anything has changed, I think [my sense of humor] has become a little more on the nose” over the years, Yoshida says. “That worries me a little bit,” he laughs.

To American eyes, an otherwise smart, self-sufficient elder succumbing to online paranoia evokes the conspiracy theories currently fueling our country’s politics. Asked about the connection, Yoshida notes that, in the context of “Teki’s” original printing in the ‘90s, “an enemy from the north” would automatically mean “Russia” to Japanese readers. Today, however, “it might mean North Korea, it might mean China, but that depends on the generation [in Japan]. In America, it might be Trump, it might be Mexicans…”

The metaphor is flexible, in short. Yoshida adds: “It’s such a pregnant word that you can, especially in this day and age, use your imagination almost boundlessly as to what an ‘enemy’ is … If there is indeed an enemy, what is that to you? We can endlessly think about that. It’s something I think about. And if it’s something that the audience happens to reflect upon after watching [my film], that would make me happy.”

The thoughtful pacing, open-ended message, and spare cinematography in “Teki Cometh” are all signs of the filmmaker’s maturing style, although Yoshida says he still has some punk spirit left in him. “I’m the type of person [for whom] there’s a direct highway from loving something to doing it,” he explains. “When I was a child, if there was a manga that I liked, I would want to draw it … it was a little bit later that I started to see films, but when I saw one that I liked, I immediately had this urge to shoot something on 8mm. As long as I have that instinct, I think I can continue doing what I do.”

“Teki Cometh” doesn’t fit into easy genre boxes. It’s nuanced and novelistic, the type of work that international cinephiles say they crave in a film landscape decimated by blockbuster franchises. Yoshida hasn’t had his crossover moment yet: His 2012 high-school portrait “The Kirishima Thing” (very loosely translated from its Japanese title “Kirishima, bukatsu yamerutteyo”) won Best Picture, and Yoshida Best Director, at the Japan Academy Awards. But Yoshida’s work rarely screens abroad — his last few films all premiered domestically, as did “Teki Cometh.” But just as the film dissolves the boundaries between its main character’s inner and outer worlds, “Teki Cometh” could break down barriers for Yoshida as well, should it find the right international distributor. Yoshida’s “enemy” could be lots of things, but this thoughtful film isn’t one of them.