I’ve seen the original “Godzilla” three times in theaters. Most films benefit from being seen on a big screen, and “Godzilla” especially so: It’s the only way to get a proper sense of scale, even if most movie screens top out at a fraction of the monster’s original 50-meter (164 foot) height. (Tracking Godzilla’s size, which varies by era, is a bit of a sport among fans.) The first time I saw “Godzilla” in a theater was for his 50th anniversary in 2004. The second was this June in Chicago. But it wasn’t until November 3, 2024, celebrating Godzilla’s 70th birthday in Tokyo, that Ishiro Honda’s kaiju classic made me cry.

It wasn’t the outcome I was expecting. I started the day on the packed plaza outside of Tokyo International Film Festival headquarters, where people waited in line for hours to try Godzilla-themed snacks — including a Godzilla crepe wrapped in a black pancake — and buy limited-edition merch as part of Godzilla Fest 2024. The crowd was large and enthusiastic, gasping and clapping at every new promotional item revealed on the festival’s main stage. (The portion of the presentation I watched included a Uniqlo tie-in and a line of Godzilla-themed cream puffs.) Off to one side, puppeteers demonstrated their craft to squeals and giggles from a group of kids, some of them in costume.

Everyone was sporting their best Godzilla merch — I was especially impressed with the woman wearing a bomber jacket embroidered with an image of Hedorah, the “smog monster” from my favorite Showa-era “Godzilla” movie. A staffer handed out paper visors shaped like kids’ mascot Chibi Godzilla; I tucked mine into my bag as a souvenir, but plenty of people, adults and children alike, put theirs on. The mood was one of celebration, delight, and gleeful consumerism. It reminded me very much of a “Star Wars” convention I attended in Chicago a few years back.

From there, I spent the afternoon walking around Shinjuku, home of the giant sculpture of Godzilla that peeks over a Toho theater in the popular entertainment district. That particular landmark is to scale — 50 meters, the size of the OG — but it blends right in with the overstimulating scenery. (Seriously, I almost missed it.) Amid that dazzling whirl of light and sound, however, fans stayed true to their king: The line at the official Godzilla store in Shinjuku was even longer than the one at Godzilla Fest, winding through the hallways of a bustling shopping mall and out the back door. The wait when I arrived was two hours.

I resolved to come back later, as I had to get back to the festival for a special event featuring Takashi Yamazaki, the director of the international crossover hit “Godzilla Minus One.” Just a few days before, Toho had announced that Yamazaki would return to the franchise for another film. But, as he told the crowd in his opening remarks, he was not there to talk about himself. He was there to support Yoshio Suzuki, one of the last surviving crew members from Honda’s 1954 original, who appeared alongside Yamazaki on stage.

Suzuki, who turns 90 this year, said in his own greeting that he was a 19-year-old sculpture student when a friend of his wrote him a letter of recommendation to work as an assistant under effects legend Eiji Tsuburaya. Suzuki recalled waking up every morning and riding his bike to Toho Studios, where Akira Kurosawa reigned as king of the lot during the shooting of “Seven Samurai.” By comparison, “Godzilla” was a modest production, whose personnel took back routes through the studio while Kurosawa held court on the main road. No one, including Suzuki and his colleagues — a crew made up of students, Toho effects men, and creators of haunted-house attractions — had any idea that they were about to create a gigantic franchise.

As the moderator pointed out, our only documentation of the original “Godzilla” suit is in black-and-white. So what color was it in person? “It was actually gray, not that different from how we imagine it to be from the film. It was gradations of gray, with brown, green and silver in parts,” Suzuki said. He described a tedious process of trial and error: He and his colleagues would begin by building wire forms around the actors, then make a metal mold from the wire, and then use that mold to sculpt versions of the suit out of different blends of rubber and plastic — both difficult to source in postwar Japan — until the right combination of elements was found.

“The suit did not move very well, it was not maneuverable. And it was very heavy,” Suzuki recalled. He said that very bright lights were needed to film the overcranked effects scenes, and the set was very hot: “[The actors] would show us the pools of sweat that had formed at their feet,” he said. Retakes were “a very big deal,” requiring new sets of props, explosives, and flash powder for each take. And yet, multiple takes were often needed because, as Suzuki pointed out, no one had ever done this before in Japan.

All this added up to two grumpy Godzillas, who took their frustrations out on lowly assistant Suzuki. “The suit actors, Mr. Haruo Nakajima and Mr. Katsumi Tezuka, were very angry,” Suzuki explained. “They would say to me, ‘I can’t act in this!’ They were too timid to complain to the higher ups, so they’d come to me and they’d punch me and kick me. Keep in mind, this was 70 years ago. It was a different era,” he said, to laughter from the audience.

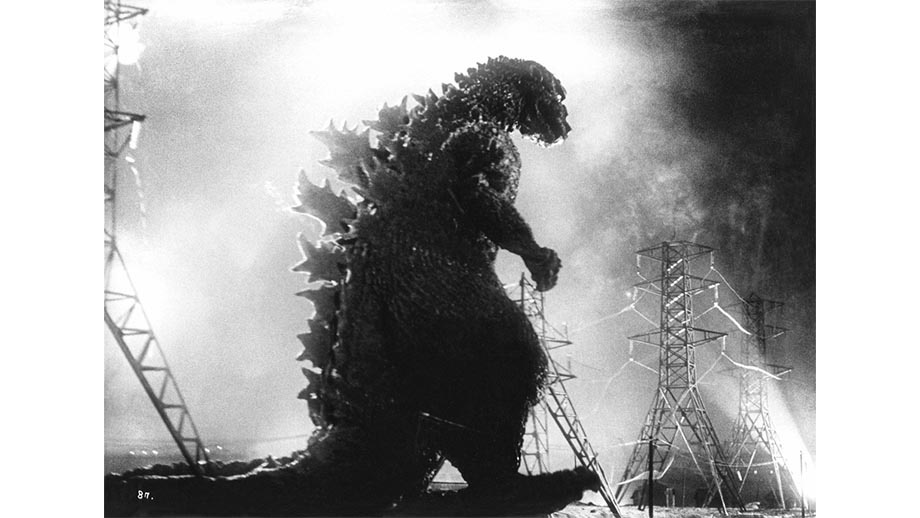

Yamazaki then described seeing “Godzilla” for the first time on TV when he was a kid: “it was very real and scary, and Ultraman [was] not going to save the day,” he said. “It was a fearsome sight to see, this kaiju destroying the town, and the tiny human beings could do nothing in the face of Godzilla.” He described “Godzilla Minus One” as being very influenced by the original film, saying, “I try to keep in my heart the message of the original Godzilla, which is anti-nuclear and anti-war. That is first and foremost in my mind” when making his own “Godzilla” movies.

On that note, the moderator paused to invite everyone in the audience who had worked on a “Godzilla” film up to the stage. There, a group of three dozen people — including directors, effects artists, suit actors, various crew members, and Nakajima’s daughter Sonoe — posed for a picture in honor of Godzilla’s 70th birthday. Then the Japanese premiere of the new 4k restoration of “Godzilla” began. (This particular restoration premiered in Berlin in February, and makes its physical-media debut in the US this month.)

The heart of “Godzilla” is the moral conflict within and between two scientists, Dr. Yamane (Takashi Shimura) and Dr. Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata). Each is torn between his work and his moral responsibilities: Dr. Yamane, a zoologist, opposes the government’s plan to kill Godzilla, protesting that we could learn how to cure radiation sickness by studying the radioactive creature. But he has no idea how to end Godzilla’s rampage, forcing him to weigh the value of potential breakthroughs against the immediate loss of human life. Dr. Serizawa, on the other hand, does know how to stop Godzilla. But he fears what might happen if knowledge of his “oxygen destroyer,” a powerful weapon he’s been keeping secret in his lab, were ever to be made public.

While these men grapple with the implications of scientific progress, Honda keeps his lens on the human side of “Godzilla.” Even in the film’s famed special-effects scenes, Honda cuts to the “tiny human beings” Yamazaki mentioned in his comments. We see civilians running in terror, attempting to break through police blockades, and ducking for cover as the city crumbles around them. Reporters say goodbye to their audience live on air. One woman clutches two small children to her chest as Godzilla gets close. “We’re going to join Daddy,” she tells them.

It’s heartbreaking stuff, and Honda underlines the parallels between Godzilla and the carnage of WWII with shots of a hospital ward packed with casualties. One child cries as her mother is taken away to the morgue. Doctors look at each other with concern as they pass a Geiger counter over a little boy. Akira Ifukube’s rousing score turns somber. This is where I started to tear up, as Yamazaki’s words resonated in my head: We as humans are so small in the face of unstoppable forces of death and destruction. What can we do? What can any of us do?

Honda’s answer is in the film’s final line. “I can’t believe that Godzilla is the last of its species. If nuclear testing continues then someday, somewhere in the world another Godzilla will appear,” Dr. Yamane says. Over the next 70 years, Godzilla would evolve from a foe to a friend and back again. He’d even become cute, as most things eventually do in Japan. But the original film still stands as a monument — and a warning. We can’t change the past. But we can change the future.