“Rob Peace,” based on a true story about the tragically short but inspiring life of a young Black American, is a kind of movie that doesn’t get made too often anymore.

Should real lives that made headlines carry spoiler alerts when somebody makes a film about them, or writes a book, both of which were the case with the title character of “Rob Peace”? I don’t know, but you should make your own determination about whether to read the rest of this review, knowing that the movie comes recommended to viewers but is not what a studio executive would call “an easy sit,” and from the very beginning has many of the hallmarks of a film that’s not going to put a big smile on your face at the end. The entire thing has the tone of an elegy or memorial throughout, including the hero’s voiceover, which has a resigned inevitability. It is also, to its credit, a movie that plays fair with the viewer, establishing very early that it’s going to honor its subject matter by being complicated, because almost nobody’s life can be interpreted just one way. The biggest success stories contain tragedies, and even the most harrowing tragedies have inspiring elements somewhere in them. Plus, some of the most fascinating characters (Rob Peace included) have flaws that pull them under; sometimes these come from good intentions that get distorted, and other times (and I think this is the case here) they fall under the heading of, “Well, if you were this person, wouldn’t you have done the same thing they did?”

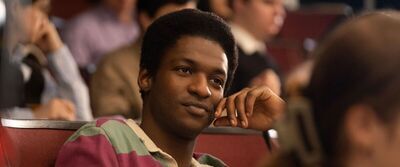

The title character, played by Jay Will with the laser-focused intelligence and charisma of young Denzel Washington, was a science-obsessed young man raised in East Orange, New Jersey, a suburb of Newark. Rob had a drug dealer father and a mom who worked three jobs to send him to a private school run by Benedictine Monks. He ended up going to Yale to study biochemistry and might’ve become a world-altering scientist had it not been for the drag of his tragic personal life: his father Skeet was sent to prison for killing two women with a handgun. The case had a lot of odd prosecutorial details that suggested police tampering (the killing firearm that was entered into evidence didn’t match Skeet’s gun, for one thing), and even though Rob was dogged by worries that his father might be guilty anyway, he worked tirelessly to free his him, diverting some of his science brain into raising and selling “designer weed” to cover attorneys’ fees and court costs during an endless series of appeals. He died just shy of his 31st birthday after neighborhood drug dealers invaded his house.

The film about Rob Peace’s life has been made in the spirit of the Black New Wave films of the 1980s and ’90s, often comedies or dramas about poor or working-class people dealing with real problems. It would not have existed without actor Chiwetel Ejiofor, who directed the film and adapted the screenplay from a nonfiction book by Jeff Hobbs, who knew the title character, and plays Skeet, a big-hearted, raucous man who loves his son but is limited, even broken, in a lot of ways. Did Skeet commit two murders? He says he didn’t, and a lot of people in the neighborhood are convinced he didn’t, and he had no criminal record of any kind prior to being arrested for the killings. Rob’s beloved mother Jackie Peace (Mary J. Blige, who’s as good an actress as she is a musical performer) won’t go so far as to say that she has doubts, only that she kept a few of the more unsavory details of Skeet’s life from their son so that he could enjoy the same privilege so many other sons have, of looking up to their fathers.

The story of Rob and his imprisoned father is the backbone of the movie but not the only element that Ejiofor focuses on. There’s a lot, and I mean a lot, going on in this adaptation, not in a bad way either. It’s impressive to consider the screenplay and direction from the standpoint of craft. It’s simultaneously an example of compression (trying to get in and out of a scene as quickly as possible, for the sake of economy and momentum) but also expansiveness (trying to make every moment do more than one thing: establish or developing characters, plant bits of foreshadowing, make comments on life beyond this one true story).

Among all the other things it is, “Rob Peace” is a portrait of a type of extraordinary individual whose prodigious gifts are yoked into service by others who don’t have such gifts. Rob’s father is the number one example—watch how he goes from being tearfully grateful for his son’s help to seeming like he feels entitled to it, and makes the lad feel guilty for not spending every waking moment living for his father. But Rob is also a beacon of what’s possible for a lot of other folks in his life, including high school and university classmates (he has the rare ability to draw people from a lot of different demographics together to party) and people in the neighborhood. There’s a even a subplot about Rob and a couple of his friends realizing early on that there’s money to be made in buying and “flipping” houses, to make a little bit of money off the gentrification that started transforming a lot of urban neighborhoods after the turn of the millennium, including East Orange and Newark’s. Rob’s got the vision, but he also has the skills, and it soon becomes apparent that the skills are part of what gave him the vision. You see this idea expressed even in little moments, like when Jackie and Rob have a household budgeting conversation and she reflexively has him do all the math.

“Rob Peace” is an ambitious, probably overstuffed movie that tries to pack an eventful life and all of its wider implications into two hours, and could easily have run three, or been a TV series. Some elements feel truncated or skipped-over, but that’s the nature of the project—another tragic inevitability. (Old movie biographies used to be able to get away with it, though: they’d give you 20 minutes on a character’s childhood, then glimpses of three or four distinct parts of their life, then wrap things up and roll the credits, and somehow nobody felt cheated.)

It’s also a populist work aimed at a wide audience. It’s a shame that movies like this no longer get mainstream theatrical distribution (unless they star Will Smith—and even then it’s a dice roll) because it seems to have been made with audience reactions in mind. Ejiofor’s direction and Masahiro Hirakubo’s editing leave space for laughs, tears, gasps, and side-talk. There are a lot of moments where Rob is knocked down by a challenge, overcomes adversity, or makes what we know is a big mistake even though he doesn’t at the time, and you just know that you’d be able to feel an audience’s collective emotional connection to the material at the cellular level if you were watching it in a theater. The best thing about this movie, though, is that it never holds your hand and tells you that if the movie feels one way about something and you feel another way, you’re somehow “watching it wrong.” If anything, it errs on the side of telling you that you’re going to come out of this movie feeling as if you’ve seen a story that doesn’t fit into one box, or even several boxes, because nobody’s life does.